By Davia Rivka

Against all odds, sixteen year old Piper Christian went to COP21 in Paris last December hoping to weigh in on the climate talks. Piper, who is president of her high school’s environmental club in Logan, Utah, knows a thing or two about how humans are causing climate change. She also knows that young people, whose lives hang in the balance, are hungry to tell their stories.

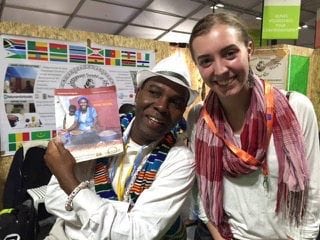

At the Climate Conference in Paris last December, Piper Christian interviewed Senna from Togo about the impact that climate change is having on his country.

I say “against all odds,” because Piper is an anomaly. Most young people don’t know what Piper knows. In February, the National Center for Science Education released a study in which over 1,500 middle and high school science teachers were asked about teaching climate change in the classroom. What they learned was disturbing.

Josh Rosenau, NCSE programs and policy director, said that one in three teachers told students that “many scientists believe climate change is not caused by humans.” Half of the teachers interviewed haven’t moved beyond the “controversy” surrounding climate change. Worse still, Rosenau said, “Three out of five teachers were unaware of, or actively misinformed about, the near total scientific consensus on climate change.”

Why are teachers so woefully uninformed? And what is being done about it?

Most middle and high school science teachers are not trained ‘climate scientists.’ Maybe they had one biology class in college. Maybe two. That’s it. So there they are in the classroom with little or no formal training.

And it doesn’t help that the science textbooks are outdated. In fact, the minute they are published, they are out of date.

What’s being done? As far as I could tell, very little is being done in a comprehensive way. Middle and high school educational climate science materials do exist — NASA, the UN CC:Learn, PBS. But who has time to pull and cull?

Which leaves most kids in the dark. Ill or misinformed. They aren’t even going to know what hit them.

But Piper — with support from her parents and teachers — does know what’s happening. And she’s not sitting on the sidelines.

When she got to Paris, she felt useless and insignificant — the decisions about her future were happening behind closed doors. Undaunted, she set up her cheap camera on a tripod and starting asking young people to tell their stories. She talked to people in the hostel, on the bus, in the streets. “Why are you here?” she asked.

She talked to kids from Togo, Sudan, Poland, Sweden, Germany. From Australia, Indonesia and Peru. Sometimes she used Google to help with translations. They told her how the rising seas were already coming in too close, how the fish were dying, how heat and drought were creating climate refugees.

Piper will have the opportunity to use her voice in the climate effort when she comes to the CCL conference in Washington this June and lobbies on Capitol Hill for Congress to put a fee on carbon. At the conference, she’ll be one of the speakers in a breakout session — Climate Action: Bringing Youth to the Table.

According to the NCSE study, teachers are hungry for more training, even the ones who deny the scientific consensus. When teachers educate, inform and empower students, Piper Christian will no longer be an anomaly. We need thousands of voices like Piper’s. The stories of young people will help turn the tide.