Don Addu (third from left) pictured with fellow panelists Chandra Farley and Sandra Upchurch to his right, and other conference attendees.

Talking climate justice with the NAACP

By Mary Gable

When we think about the current and future effects of climate change, it’s easy to focus on the big picture: rising global temperatures. More severe weather for everyone. Disappearing coastlines worldwide.

Indeed, a changing climate will touch the lives of everyone on earth. But it’s also important to zoom way in and consider the effects at the level of the community or the neighborhood. When you do, it quickly becomes clear that not all will feel the effects equally. And in many cases, those who did the least to cause the problem will be hurt the worst by it.

The climate justice movement is a response to this reality, connecting the need for action on climate change with the fight for equality and human rights. Climate justice and environmental justice organizations have been doing vital work for decades, from keeping extractive and polluting industries out of their neighborhoods to promoting community-based renewable energy programs.

Examples of climate injustice are apparent on a global level, such as between high-emitting developed countries and the island nations they may someday wipe off the map. It was on display during this month’s youth protest, when 1.4 million young people from 123 countries took a stand against their forebears’ climate inaction, the consequences of which they will cope with for their entire lives.

In the U.S., numerous injustices exist between racial and socioeconomic groups. For instance, Americans of color are more likely than white Americans to be exposed to particulate matter pollution. That’s in part because coal-fired power plants are more likely to be located in communities where African Americans live. A recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences demonstrated that while people of color disproportionately feel the effects of pollution, that pollution is disproportionately caused by the actions of whites.

Sandra Upchurch, SACE

Sharing perspectives and learning from others

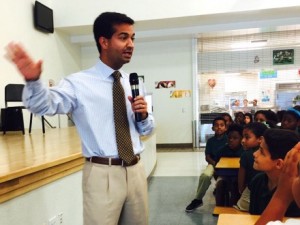

Many organizations have a specific focus on addressing these types of inequities. Citizens’ Climate Lobby prioritizes relationships across our movement and is interested in building connections to help these groups accomplish their goals. To that end, Don Addu, CCL’s Southeast Director, recently appeared on a panel at the Tennessee State Conference of the NAACP’s annual Race Relations Advocacy Summit.

During the 2018 Tennessee Energy Freedom Tour, Addu met Ameera Graves, the NAACP Student Sponsor at Lane College, a historically black college in Jackson, Tenn. They began a dialogue about climate change and environmental justice, and when the Tennessee NAACP chose to devote part of their annual summit to a discussion of these issues, Graves asked Addu to contribute.

Addu represented CCL on the panel, alongside Chandra Farley, Director of Just Energy with the Partnership for Southern Equity (PSE); and Sandra Upchurch, Energy Justice Manager for the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy (SACE). PSE empowers individuals and organizations to promote prosperity through energy equity, economic inclusion and equitable development in Atlanta and across the South. SACE works to promote energy efficiency and renewable energy by engaging communities and policymakers throughout the Southeast.

Chandra Farley, PSE

The event was less about the panelists holding forth about their own organizations and more about conversation among all those present. With Graves as moderator, panel attendees divided into groups, with each group given a set of terms to define, like environmental racism, energy burdens, or rate hikes. Participants worked together to define the terms, and the three panelists answered any questions that arose.

The group discussed specific pieces of legislation, like the Energy Innovation & Carbon Dividend Act, as well as broader ideas like the Green New Deal—and how both can meet the needs of communities of color.

“During the panel, I asked for a show of hands of who had used fossil fuels in the past 24 hours,” Addu says. “As I expected, everyone in the room had.”

“The reason why? People don’t have any other choice. A price on carbon, like that proposed by the Energy Innovation Act, would fix this market failure. And it would make other policy proposals, like training for new energy jobs and investments in sustainable infrastructure, more likely to succeed.”

The Energy Innovation Act would also benefit lower-income Americans. An individual’s carbon footprint typically increases along with income, and many households would see more benefit from carbon dividends than they spend in increased costs of goods. A working paper published in 2016 exploring the financial impact of the fee-and-dividend approach found that most low-income Americans, as well as minority racial groups, would benefit financially from such a policy.

A carbon fee and dividend would not only help people pay their bills—it would help shut down the coal-fired power plants that are making so many Americans sick. By reducing emissions and pollution at the source, a policy like this would begin to correct some of the environmental inequities that have shaped the lives of people of color for generations.

Supporting the movement

CCL will continue to engage with organizations that are working on solutions for climate justice. Addu attended the National Environmental Justice Conference in D.C. in March and was invited to attend the Tennessee NAACP’s state convention in November. Other CCLers are part of the Climate and Environmental Justice Action Team on CCL Community, which currently has more than 250 members.

Just as America faces a choice regarding how boldly to address the crisis of climate change, we also face choices about whom our solutions will help and whom they will leave behind.

Courageous climate solutions can do more than stop melting glaciers and rising tides. They can also fix the injustices woven into society’s fabric—leaving us with not just a livable world, but a world that’s fairer than the one we had before.