A carbon tax is right for environment and economy

By Jerry Hinkle, CCL Economics Policy Network

Economists are overwhelmingly in favor of charging for carbon pollution via a tax or fee. This blog post explores the many reasons why. We start with the theoretical—how Pigovian Taxes (1) improve the economy. Then to the practical, we discuss the impact of such taxation on near-term measures of economic vitality such as GDP and employment. We describe how the climate and non-climate benefits of such taxation greatly outweigh any cost. And finally, why economists prefer a tax to regulation is explained.

Pigovian taxes

Why do economists insist an appropriate Pigovian Tax improves the economy? Economic theory makes clear polluting should not be free. Accurate price signals are vital to an economy producing the right amount of goods and services. When the production or consumption of a product (e.g., gasoline or coal-generated electricity) brings costs (e.g., climate change damages, health risks) that are not reflected in its market price (i.e., are external to the market), the good is said to contain an “externality” or “external cost.” Because the market price does not reflect the external cost, the price of that product is too low, and too much of the product is produced.

The remedy is simple: place a fee on the product (a Pigovian Tax) equal to the external cost to correct the prices. This is referred to as internalizing (to the market price) the externality. As a result of the tax and higher price, less of the product is produced, and the market economy becomes more effective at producing the right goods. This was done with cigarettes: smoking increases health care costs paid for by the government, so the product is taxed, in part, to have the market price reflect these external costs. Fewer cigarettes are produced and consumed as a result.

But climate is the granddaddy of all externalities and the failure to account for the cost of burning fossil fuels is considered “the greatest market failure the world has ever seen” (2). External costs are over $500 billion annually (3) (climate damages only) in the U.S. alone, representing about 2.8% of GDP. To improve the market economy, when consumers choose between a more or less fuel efficient car or appliance, and when a utility invests in a new power plant, it’s critical that the market prices informing their decisions reflect the full cost of the product. This then allows the economy to produce the right goods and puts us on a path toward a cleaner, more stable future.

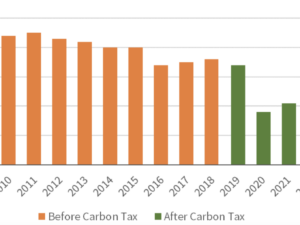

GDP

How does such a Pigovian Tax affect GDP? As noted in a recent CCL blog post, much economic analysis of revenue neutral carbon taxes (RNCT) has been published this year. The consensus is that the GDP impacts are minimal, and can be positive or negative depending largely on how the revenues are distributed. The authors acknowledge that the models are imperfect, and that actual economic results are likely to be better than the models predict, so results such as those from REMI are feasible. There is an “equity/efficiency trade-off”: using the revenue to cut other taxes may increase GDP (i.e., is more “economically efficient”) but is regressive (hurts the poorest and increases inequality), while returning the revenue equally to households as CCL does may reduce GDP slightly but is progressive (helps the poorest).

Jobs

Most of these models assume ongoing full employment, so they don’t have the capability to calculate the impact on jobs. We do know that in these simulations, the predominant outcome is that coal is replaced by renewables and energy efficiency technologies, and that these generate far more jobs than coal. One study synthesized the results of 15 estimates, and found that generating a unit of energy from wind, solar, or energy efficiency efforts creates between 1.5 and 8 times more jobs than coal (4). We expect that a RNCT policy will be a job creator as the REMI study indicated, and additional studies are in the works to explore this.

Benefits of reduced emissions

Why do economists insist a Pigovian Tax is right for the economy if the impact on GDP and Employment is uncertain? Simply stated, the models don’t include the benefits of reducing emissions such as reduced health and climate costs (5), and these are expected to be far greater than any GDP loss. For example, in a recent and extensive analysis (6), climate benefits are generally estimated to be at least twice the economic costs and health benefits at least three times the costs. These climate and health costs will reduce GDP both sooner and later, whether they are reflected in the model or not. This is why economists are crystal clear that appropriate Pigovian taxes improve the economy as well as the environment.

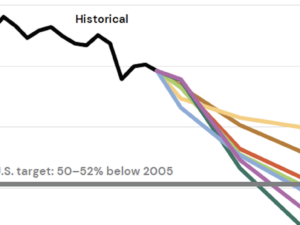

Efficiency: Tax vs. regulation

The economic literature makes clear that correcting market prices through a tax is far more economically efficient than regulation in reducing emissions, so that a given level of reductions are achieved at lower cost. The efficiency stems from giving market participants the ability to choose the least cost path for reducing emissions. As a pertinent example, the Clean Power Plan (CPP) was designed to reduce U.S. emissions by 32% by 2030 at a cost estimated by the EPA at between 0.04 and 0.07% of GDP per year (7). According to a recent analysis by Columbia University of a RNCT similar to CCL’s (8), the policy reduces emissions between 39%-46% by 2030 at a cost of 0.03% of GDP per year over that time. So utilizing a carbon price generates greater reductions at significantly less cost than regulation.

In sum, economists are clear that charging for pollution improves the economy. If the tax is revenue neutral, GDP is minimally affected, jobs likely grow, and the climate and health benefits are substantial. A RNCT is clearly a win for the environment and the economy.

Footnotes:

- Named after economist Arthur Pigou, more background is in this Wikipedia entry.

- This characterization is from Sir Nicholas Stern, former Chief Economist of the World Bank and author of the Stern Review.

- US GHG emissions were in 2016, and had been at least this high since 1993. The US Interagency Working Group (IWG) on the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) estimated external costs at between $15 and $150 a ton (average of $82.5). This yields an approximate US external cost of $537 billion. The current EPA has estimated a lower SCC, though those figures are quite controversial.

- Specifically, generating energy from wind, solar from thermal, solar from PV, and energy efficiency requires 1.5, 2, 8 and 3.5 times the number of jobs as generating that energy from coal.

- The climate benefits are very apparent, but far more difficult to estimate, so are kept separate.

- See pages 114-119, in Confronting the Climate Challenge: US Policy Options, by Larry Goulder (Stanford) and Marc Hafstead (Resources for the Future), January 2018, Columbia University Press.

- In 2016 (Obama Administration) the EPA estimated the cost of CPP to be $7 billion a year, and in 2018 (Trump Administration) the EPA estimated the cost at $14 billion a year).

- The policy sets a carbon price of $50/ton rising at 2%/year, and contains a border carbon adjustment.

Jerry Hinkle is an economist who holds master’s degrees in Economics and Climate Policy.

The Economics Policy Network is a team of CCL leaders and supporters with a diverse background in the field of economics. These network contributors write regular guest posts, offering thorough insight into topics that fall within their expertise. Their resources are available in the form of white papers on CCL Community.