In response to the proposed weakening of the Office of Congressional Ethics last week, constituents across the country picked up the phone and called their representatives.

By Flannery Winchester

Last week, the 115th Congress got off to a dramatic—but important—start. Important not because of what the Congress did, but what the constituents made possible. Here’s what went down: In a closed-door meeting last Monday night, House Republicans agreed to a proposal that would limit the capabilities of the Office of Congressional Ethics. The proposal was intended to be part of the rules package for the new Congress, and it would have brought the independent ethics office under the oversight of the House Ethics Committee, effectively compromising the OCE’s independence. Also, according to Politifact, “Other provisions of the amendment would keep staff from speaking publicly without the House Ethics Committee’s consent, prevent the office from investigating anonymous tips, and rename it the ‘Office of Congressional Complaint Review.’”

Even if those changes had legitimate motivations behind them, it quickly looked bad in the press. One party gains power in the House, Senate and the White House, and its first order of business is to hobble a bipartisan, independent ethics group? It’s tough to put a good PR spin on that.

By Tuesday, House Republicans were backing away from the proposal. It doesn’t appear in the final rules package at all. So what happened?

Outpouring of organic advocacy

Well, you happened. We happened. A whole lot of public pressure happened. Brad Fitch, the president and CEO of the Congressional Management Foundation, has served on the Hill and worked as a researcher and consultant for Congress. He’s seen these waves of public pressure arise before, he explained.

“I put them in two categories. There’s what I call organic advocacy and directed advocacy. Most advocacy going to Capitol Hill is directed, meaning a group like the American Medical Association or the National Rifle Association sends an email out to their members, supporters or employees and says, ‘Please forward this out to Capitol Hill.’ Occasionally, every few years, we’ll get organic advocacy.”

At their staff meeting, the Congressional Management Foundation decided to do some digging and find out what advocacy type made the difference last week. “We talked to the congressional offices,” Fitch said, and, “it sounds like it was a little of both, but it was mostly organic. The way we know is if people are usually talking off the same script, then it’s directed—they have the same message and the same talking points over and over again. But in talking to congressional staff, we heard ‘No, we just had a lot of cranky people calling us.’”

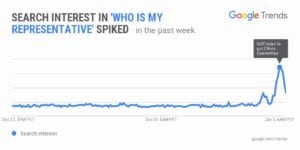

Trends spiked on Tuesday, as news spread of the proposed changes to the Office of Congressional Ethics. Image courtesy of Google Trends via Twitter.

The pressure was amplified by an avalanche of negative press and two tweets from President-elect Trump. But those factors can’t take all the credit for the GOP’s backtrack: Google showed a spike in searches for the phrase “Who is my representative” on Tuesday morning. Across the country, constituents were turning to Google to identify their reps, and presumably many of them followed through with a call to that representative’s office—and a few choice words.

Be ready to act

“I think for CCL members, there’s a lesson here,” Fitch said. “The lesson is that you have to be nimble. You have to act quickly. We realize that people have busy lives, but this proves again that those people who are ready to act when action is required are the ones who win the day.”

Not only are we ready to act now, but we’ve already been acting on the topic that is closest to our hearts: climate change. In 2016, CCL volunteers held at least 1387 meetings with representatives in Congress and wrote more than 40,000 letters to Congress. With last week’s example in mind, we’ll continue our respectful, persistent communication with all our representatives, knowing that it really does make a difference.