Fighting climate change and opposing Russian aggression are compatible goals

By Tony Sirna

The Russian attack on Ukraine is a tragic situation that is upending geopolitics and our global energy systems. Naturally, the question arises about how this affects climate politics and how climate advocates should be talking about this.

The situation

First I want to acknowledge that things are changing day to day and week to week on this topic, so it is hard to keep up with current events. It’s worth keeping in mind that this information is subject to change.

On Feb. 24, Russia invaded Ukraine. Western countries have imposed fairly strong sanctions on Russia that are already affecting their economy but do not seem to be slowing their military actions in Ukraine down. For the most part those sanctions have avoided targeting one of Russia’s main economic drivers, their oil and gas industry, until Mar. 8 when President Biden announced he was banning the import of Russian oil.

Europe is in a very tough position, as they get a significant amount of their oil and gas from Russia, which makes it difficult for them to take similar steps to quickly ban imports. Yet, much of Europe fears that Russia could shut off their supply at any time to put pressure on the continent to drop sanctions. This means that while Russia can wield energy security as a powerful weapon against Europe, they are also economically vulnerable if the world sets up an embargo on its fossil fuel exports.

All of this instability is leading to a spike in oil prices globally, as well as methane gas prices in Europe. This is on top of the already existing high prices that resulted from the quick economic recovery from the pandemic, supply chain issues, and extreme weather events (and decisions by oil cartels to limit production). Unfortunately, high energy prices mean more money flowing to Russia, and to the fossil fuel companies in general who are showing huge profits right now.

The @LATimes has the right idea with this editorial. We can resist thugs like Putin by transitioning quickly off fossil fuels, and passing the climate provisions of #BuildBackBetter will speed that transition.

clean energy = energy independence https://t.co/gWz3KoOrhK

— Citizens’ Climate Lobby (@citizensclimate) March 10, 2022

CCL has called for transitioning quickly off fossil fuels and passing climate provisions.

How does this impact climate politics?

Right now there are two competing narratives.

One, coming from fossil fuel proponents, is that given this crisis, the answer is to “drill, drill, drill,” with the idea that more U.S. oil and gas production can solve this problem.

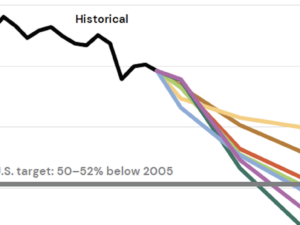

The other, coming from climate advocates and now from the President himself, is that the only solution that truly protects us from energy price spikes and energy geopolitics is weaning off the dependence on fossil fuels (as is summarized in this NYT article). Biden said recently, “This crisis is a stark reminder that to protect our economy over the long term, we need to become energy independent. It should motivate us to accelerate a transition to clean energy.”

Let’s dig into those narratives and look at how we can support the latter and respond to the former.

CCL Executive Director Madeleine Para already has an op-ed on this very topic that volunteers are getting published in local papers around the country. Check out her piece for some key talking points.

View this post on Instagram

CCL’s Executive Director Madeleine Para recently wrote an op-ed about clean energy and Russia.

One key point from Madeleine’s op-ed to highlight says, “Energy independence cannot come through increased domestic oil and gas production. In fact, the U.S. is already a net exporter of energy, yet oil is a global commodity and our energy prices are affected by the actions of other major players like Russia and Saudi Arabia.”

This is a key point in any conversation about the Russian invasion or energy prices in general. No matter how much we produce in the U.S., we are still beholden to global oil prices. Increased domestic production might lower prices a little, but it would have a minimal impact on the huge global market.

It’s important to continue the fight for a transition to clean energy.

For Europe, the challenge is that getting off of Russian methane gas (aka natural gas) quickly would require solutions that can meet their demand by next winter. The European Union has announced plans to cut dependency on Russian gas.

The IEA plan says that Europe can reduce its need for Russian gas through energy efficiency, electrification, conservation, increasing production from existing nuclear plants, and accelerating deployment of wind and solar installations. All of these can reduce demand this year. Climate advocate Bill McKibben has suggested President Biden could invoke the Defense Production Act to ramp up the manufacture of heat pumps, which rely on electricity instead of gas, and ship them to Europe. Rewiring America fleshed out the plan and now the Washington Post reports the White House is seriously considering the plan. Europe can also find alternative sources of gas and increase storage. Together, these initiatives can reduce imports of Russian gas by 1/3 to 1/2 this year, which is significant and could lower their gas prices dramatically (and in turn the money flowing to Russia).

You can find more Rewiring America posters here.

By contrast, export and import terminals for Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) take three to six years to build and so will not help in the short term, and would lock Europe into using methane gas in the longer term. Such a fossil fuel infrastructure build-out would run up against Europe’s climate targets and lead to “stranded assets” as clean energy sources replace fossil fuels.

As for calls to “drill, drill, drill,” in the U.S., these are primarily attempts to expand the fossil fuel industry in ways that won’t actually help with the current situation and would ultimately be bad for the climate.

Vox has a good piece dispelling some of the myths behind this effort. One key quote explains that. “In other words, now that companies are making handsome profits, they’re using that extra cash to reward investors and pay down debts, not invest in new production.” In short, oil companies make more money when oil prices are high and don’t have much incentive to drive prices down even if they could.

It’s really essential for the climate that we not allow this current crisis to drive an increase in fossil fuel infrastructure that would last for years or even decades. As the Vox article notes:

“The biggest risk is if the U.S. and Europe respond to this crisis by over-investing in the future of fossil fuels. Actions like building LNG terminals and approving new leasing don’t help in the short term when people are struggling to pay high bills. It doesn’t achieve energy independence. But it would lock the world onto a dangerous path for climate change.”

Basically, proposals to open leasing on public lands, build pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure will not help lower current energy prices in the U.S. as they would not increase production quickly. The U.S. does not have the capacity to increase production in the short term, but countries like Saudi Arabia do; there has even been some consideration of opening up oil trade with currently embargoed countries like Venezuela and Iran. It seems we may be stuck with high energy prices for a while.

@citizensclimate Why are gas ⛽️ prices so high? #ukraine #russia #putin #fossilfuels #cleanenergy #Climate #climatechange #Climatecrisis #carbontax #priceoncarbon #solar #wind ♬ Pieces (Solo Piano Version) – Danilo Stankovic

CCL has been hard at work discussing what the war on Ukraine means for the climate movement.

High oil prices are not the same as a carbon price

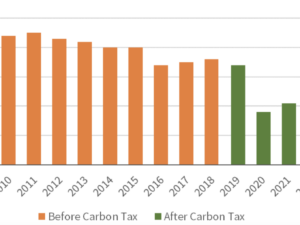

Some pundits have lately been seen equating high oil prices with carbon pricing, on the notion that high prices will reduce demand and could lower emissions. It’s true that the current high prices make cleaner solutions like electric vehicles very attractive and so could inspire electrification and shifts to clean energy. But there are clear differences between a high price on the global oil market and carbon pricing.

For one, with a carbon fee and dividend, the fossil fuel companies pay a fee and the money goes to households to support them through the transition to clean energy. With high oil prices households pay the price and the money goes to higher oil company profits. One is good for most households while the other is bad.

Secondly, a carbon price will encourage a switch to clean energy and some level of conservation. Higher oil prices might do the same, but they will also inspire investments in producing more oil, thus locking in more fossil fuel infrastructure and more future emissions.

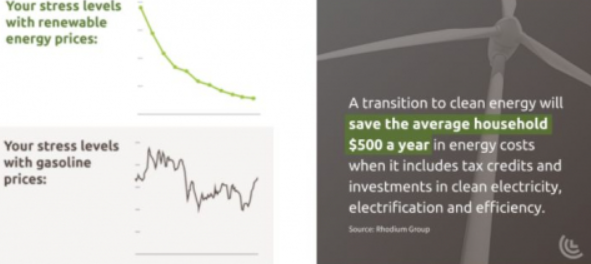

Thirdly, there is a huge difference between unstable and unpredictable price spikes and a steadily rising carbon fee. Gasoline prices have increased by at least $1.50/gallon in the last year because of market volatility, extreme weather, the pandemic, and now a war. By comparison, a carbon price might only add 10 cents to a gallon of gas in a year, in a steady and predictable way that would allow consumers to plan ahead as they transition to a zero-emissions vehicle. At the same time, prices for renewable energy have been falling rapidly, and, in general, electricity prices are quite stable. Electrifying vehicles and homes will in many cases save people money and protect them against frequent fossil fuel price spikes.

This means more inflation

As is often the case, war and instability are other drivers of inflation, on top of the inflation we’ve already been seeing. It might seem like high inflation would argue against carbon pricing but carbon fee and dividend would not have a big impact on inflation and the resulting switch to affordable and clean energy would reduce costs.

The infographics below drives home the point that renewable prices are stable and cheaper than gasoline prices and that households will save money.

As the Biden administration has been saying “In the long run, the way to avoid high gas prices is to speed up, not slow down, our transition to a clean energy future. The reality is we can’t drill our way out of dependence on a global commodity that’s controlled, in part, by foreign nations and their leaders, including Putin. The only way to eliminate Putin’s and every other producing country’s ability to use oil as an economic weapon is to reduce our dependency on oil.

What can you do now to fight against Putin and for the climate?

First, support the valiant people of Ukraine. Second, write Biden and your members of Congress and tell them you want them to pass legislation that will speed the transition off of fossil fuels. Third, consider ways to reduce your consumption of fossil fuels: electrify your home and turn down your thermostat (or turn it up if you are running air conditioning) and switch to an electric vehicle or transit or walking/biking or just drive less. Then, help others reduce their fossil fuel use by teaching them how and helping pass local and federal legislation.