CCL’s Research Department modeled carbon pricing policies with the Energy Policy Simulator, finding that these policies can cut greenhouse gas emissions very quickly and benefit public health.

By Rick Knight, CCL Research Coordinator

Any climate policy worth fighting for must do two things well: reduce carbon emissions and protect the poor. These are CCL’s so-called “bottom lines.” So how do we know if a steadily rising price on carbon will measure up?

With neither a crystal ball nor a time machine at our disposal, the only way to predict future emissions is through mathematical modeling.

Sophisticated modeling tools have been developed and applied mostly behind the walls of academic institutions and think tanks with access to the powerful computers needed to run complex CGE models.

But in recent years, some online climate policy simulators have appeared. CCL volunteers may already be familiar with En-ROADS, a simulator from Climate Interactive that predicts global emissions and energy use. However, another online tool that has drawn attention lately is the Energy Policy Simulator (EPS) from Energy Innovation Policy & Technology LLC (EIP&T).

Energy Policy Simulator

EIP&T was founded in 2012 as a consulting firm. In 2015, they developed and released their Energy Policy Simulator as an open-source policy modeling tool. Unlike En-ROADS, which simulates global emissions, the EPS offers a U.S.-only model that can represent the impacts of Congressional bills relevant to CCL’s advocacy.

The EPS got some attention in June 2020 when it was referenced in a majority report from the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. EIP&T simulated a wide-ranging legislative package for 23 of the nearly 200 bills named in the report, and claimed 88 percent emissions reduction by 2050.

Given this development, CCL’s Research Department felt it was timely to delve into the EPS, see if current carbon pricing bills could be simulated, and see how well they would perform.

Web-based modeling tools like the EPS and En-ROADS are much simpler in structure than CGE models, which can take hours, days, or even weeks to bring all the interdependent variables into equilibrium. The EPS returns results very quickly, and thus allows the user to quickly compare policy parameters (e.g., a carbon price), but does not have the ability to resolve complex economic feedbacks as thoroughly as the CGE models can.

With those caveats in mind, here is how we have simulated the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act (Deutch), America’s Clean Future Fund Act (Durbin-Newman), the MARKET CHOICE Act (Fitzpatrick), and the Save our Future Act (Whitehouse) using the online EPS.

Carbon price

To enter a carbon price into the EPS, the user has to define a price trajectory out to 2050. The maximum carbon price allowed is $300 per metric ton of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e). Because all these bills stipulate price-per-ton increases for missed targets, we manually iterated between the emissions results and the carbon prices and then adjusted accordingly. These bills also include rebates for CO2 capture and sequestration (CCS), so we captured that impact by consulting published CCS cost estimates and then assumed deployment would start when the carbon price met the breakeven cost for each fuel or sector.

For three of the four bills, the carbon price hit $300 before 2050, so to avoid inaccuracy based on that limitation, we are reporting results only up to 2040.

Complementary policies in place today

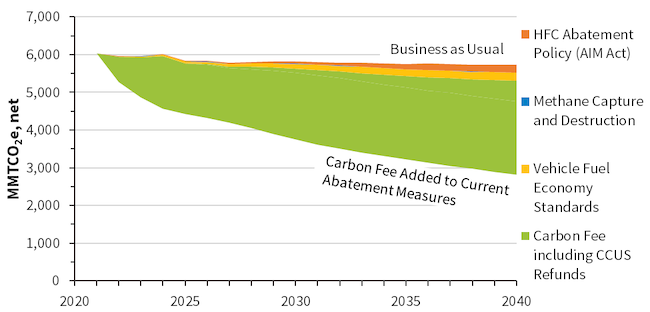

There are also three climate-friendly complementary policies in place that we didn’t have in 2020! First is an HFC phase-down plan, part of the AIM Act that became law in December 2020. Another is a methane abatement rule that had been repealed but is now being restored. Finally, the Biden administration has moved to restore the auto mileage regulations (CAFE standards) that had been weakened under the previous administration.

To reflect this, we’ve included these complementary policies in all our simulations, including Business As Usual, which we designate as “BAU-C.”

Carbon emissions

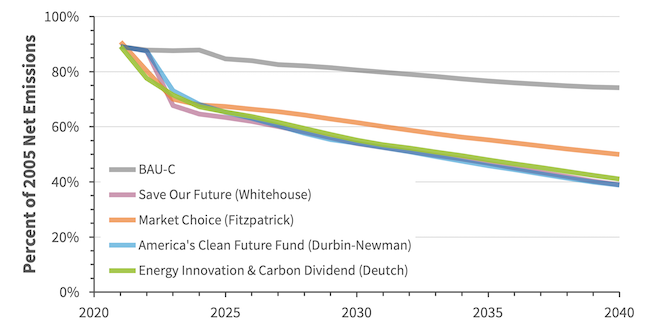

As we’ve seen from other modeling reports, the EPS shows that any one of the four currently active carbon pricing bills would drive emissions down far more quickly and deeply than BAU-C.

It predicts that through 2040, the Deutch, Durbin-Newman, and Whitehouse bills would all cut carbon emissions by 59 to 61 percent below 2005 levels. The Fitzpatrick bill would lag them a bit, reducing emissions by 50 percent below 2005. It’s worth noting that even the BAU-C path results in 17 percent lower emissions, primarily due to the complementary policies mentioned above.

How important is the carbon price in achieving these cuts? The wedge diagram below is for the Deutch bill, and it shows that 89 percent of the reduction in emissions is due to the carbon fee. This is consistent with the predictions of mainstream economists, who universally agree that pricing carbon is an essential component of climate policy.

Pricing carbon cuts air pollution

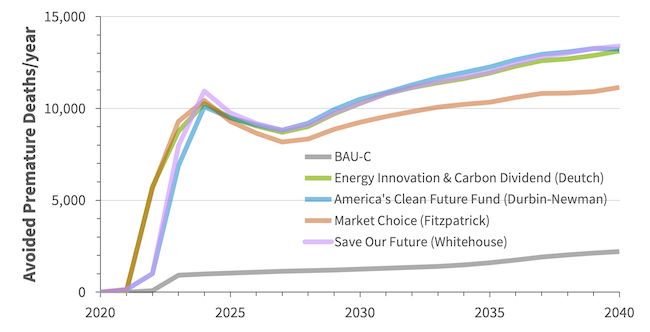

Another major benefit of reducing carbon emissions will be concurrent cuts in air pollution that still take a toll on public health, especially in frontline communities. Mainstream models have shown that pricing carbon can rapidly cut air pollutants like PM2.5, NOx, and SO2, and the EPS illustrates just how many lives this will save.

The chart below indicates that while BAU-C policies alone will prevent one to two thousand premature deaths per year, putting a price on carbon will save 10 times as many, and do so almost immediately.

By 2040, according to the EPS, a carbon pricing plan will prevent over 400,000 heart attacks, over 9 million asthma attacks, and nearly 200,000 premature deaths due to cleaner air and other climate benefits. On a monetized basis, this would save our economy over $8 trillion in health costs by 2040.

It’s clear from these simulations that placing a strong, rising price on carbon cuts greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants, and does so very quickly.