On fourth and goal, budget reconciliation needs a carbon price to score

By Rick Knight

Imagine you’re playing in the Super Bowl. Your team has the ball 10 yards from the end zone in the fourth quarter, down by four points with 10 seconds left, and it’s fourth down. Everyone knows you’ve got one play to get into the end zone. The coach sends in the play: kick a field goal.

Why would he do this? So that your team will lose by less? Well, it’s still possible to win. Maybe the holder will fumble the snap, and the kicker will then pick it up and run into the end zone. Anything is possible!

On Oct. 27, President Biden announced that the Senate had agreed to a framework for a budget reconciliation package including policies capable of meeting his goal of 50% reduction in carbon pollution below 2005 levels by 2030. This was a critical step forward to establish U.S. leadership just prior to the big COP26 climate conference in Glasgow the following week.

The President’s confidence in our ability to meet this goal was based partly on a report by the Rhodium Group (1). The top-line message from that report is that there is a path forward that has a chance of getting us close to 50% emissions cut below 2005 levels, but it requires much more than the policies in the reconciliation package, including new EPA regulations, climate legislation at the state level, and even voluntary private-sector commitments.

The Rhodium report makes it clear that the risks of failure to meet the goal are many and serious. Just as one example, any new climate regulations under the Clean Air Act will be challenged in court, delaying their implementation for years and possibly striking them down altogether. That legal risk has, just in the last few weeks, further increased with the news that the Supreme Court has agreed to hear a challenge to the EPA’s foundational authority to regulate greenhouse gases. Legal observers believe that at least five of the Justices are inclined to overturn that authority, which would pull the rug out from under many of the regulations Biden is relying on to cut emissions beyond what is possible under the reconciliation bill.

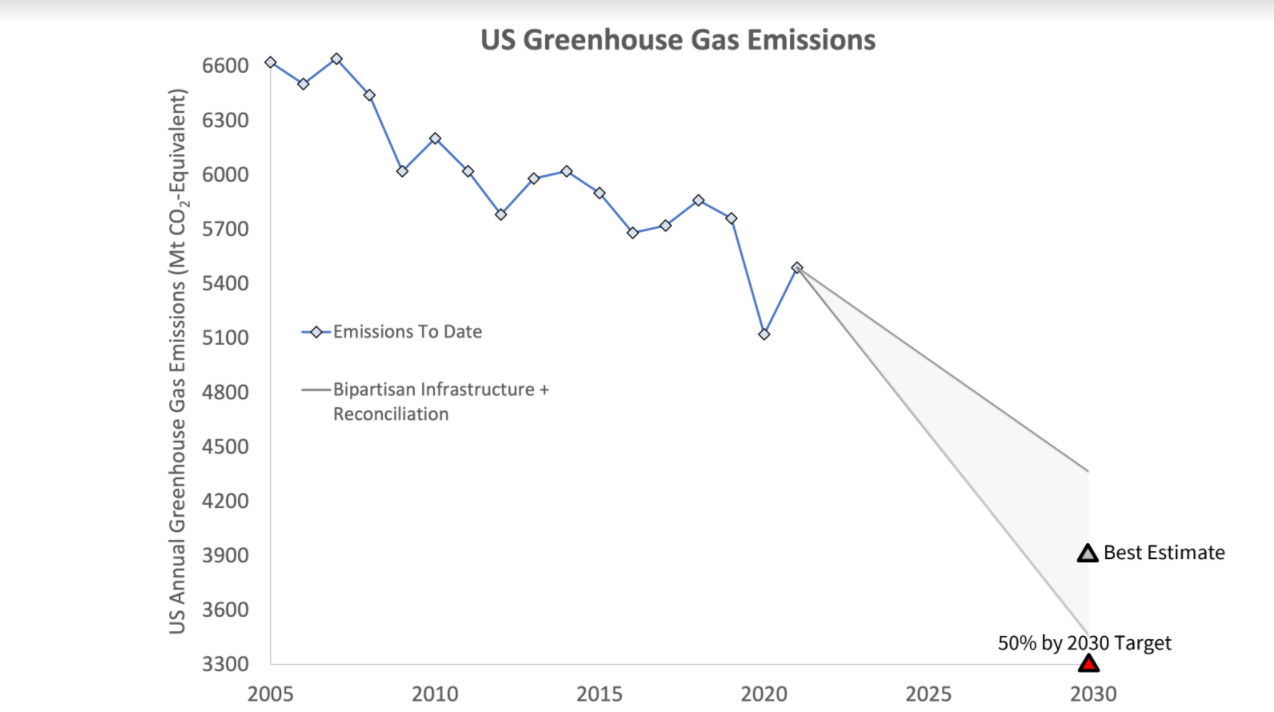

The CCL Research Team reviewed analyses from seven different energy modeling sources (2), putting them all on the same basis — net CO2-equivalent emissions. We found that under their business-as-usual scenarios — if budget reconciliation fails altogether — U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 would be lower than 2005 emissions by about 22%, or 1.4 gigatons (Gt). So, getting those cuts to 50% (or 3.3 Gt lower) by 2030 requires an additional 28%, which translates to about 1.9 Gt of CO2-equivalent. That’s how much greenhouse gases must be cut beyond what current policies, not counting those in the reconciliation bill, can do.

Previous modeling by Princeton and Energy Innovation analysts suggests that what’s currently in the Build Back Better legislative package could cut around 1 Gt. Another 0.2 Gt could be achieved by a fee on industrial methane leakage that is still under consideration. If both of those are enacted, they could get the U.S. to 40% below 2005 levels by 2030, leaving about 0.7 Gt still to be cut in order to reach the 50% target.

Keep in mind that this does not mean the reconciliation package will cut 40% from the emissions we are currently putting into the atmosphere. Comparing the cuts to 2005 emissions — one of the highest emissions years in U.S. history — makes that achievement sound bigger than it really is. But the expected cuts in this plan would actually be only about 28% below current emissions, about two-thirds of what’s needed to fulfill America’s promise for 2030.

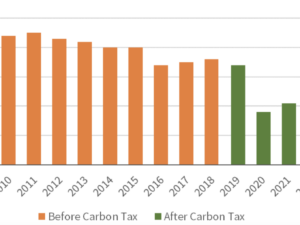

We conclude that there remains a serious need to reliably cut emissions well beyond what the current reconciliation outline is likely to achieve. Fortunately, a carbon fee with cash payments allocated to households has near unanimous support among Senate Democrats and, depending on how strong it is, could more than make up for the remaining emissions gap. A previous Rhodium study showed that a carbon polluter fee alone could cut energy-related CO2 emissions by 33-41% below 2005 level with no additional policies. That does not mean adding a carbon fee to the reconciliation package would slash emissions an additional 41% below what the legislative plan can achieve — there would be some redundancy with other policies — but a Resources for the Future analysis of the reconciliation package in September 2021 found that adding a carbon fee could improve CO2 reductions from 38% of 2005 emissions to 51%.

Consequently, we can say with some confidence that a robust carbon fee would be a powerful insurance policy to smash through that 50% by 2030 target. Indeed, the Rhodium report named a carbon price first among “additional policy opportunities” that should be considered if Build Back Better provisions “come up short due to legal challenges or implementation delays.” We agree.

The world stands at a truly critical juncture on climate, and we can’t afford to come up short. We can’t settle for a field goal. This is a contest we have to win, and the carbon price is the play that can get us into the end zone.

CCL’s Research Team discussed this topic during the Grit and Gratitude virtual conference. You can watch this related session below.

Footnotes:

- Note: this report was issued October 19, when the budget reconciliation bill was still nominally at $3.5 trillion.

- Resources for the Future (RFF), Energy Innovation Policy & Technology (EIP&T), U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP), Rhodium Group (Rhg), Princeton University Zero Lab (PUZL), and Climate Action Tracker (CAT).