Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions are down, but so is public support for its carbon pricing policy. Let’s explore why.

Perception gap plagues Canada’s carbon price

By Rick Knight, CCL Research Coordinator

Canada’s carbon pricing law, which went into effect in mid-2018, features an annually rising carbon price, with 90% of the revenue rebated to households. Public support has historically been strong. As of July 2023, 10 of Canada’s 13 provinces or territories have adopted the federal plan, and the Niskanen Center reports that 80% of households come out ahead when receiving the rebate.

Sounds good! Indeed, my last blog post on this topic was titled “Canada leads the way on carbon pricing.”

But over the last year, public support for the carbon tax has dropped considerably – from 56% in 2021 to 45% this year. What happened?

Politics happened. A national election is scheduled for 2025, and Prime Minister Trudeau’s chief opponent, Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre (pwa-lee-EV) is now leading an anti-carbon-tax campaign, summarized in the slogan “Axe the Tax.”

What’s the basis for this opposition? Is it because the carbon price has failed to reduce emissions?

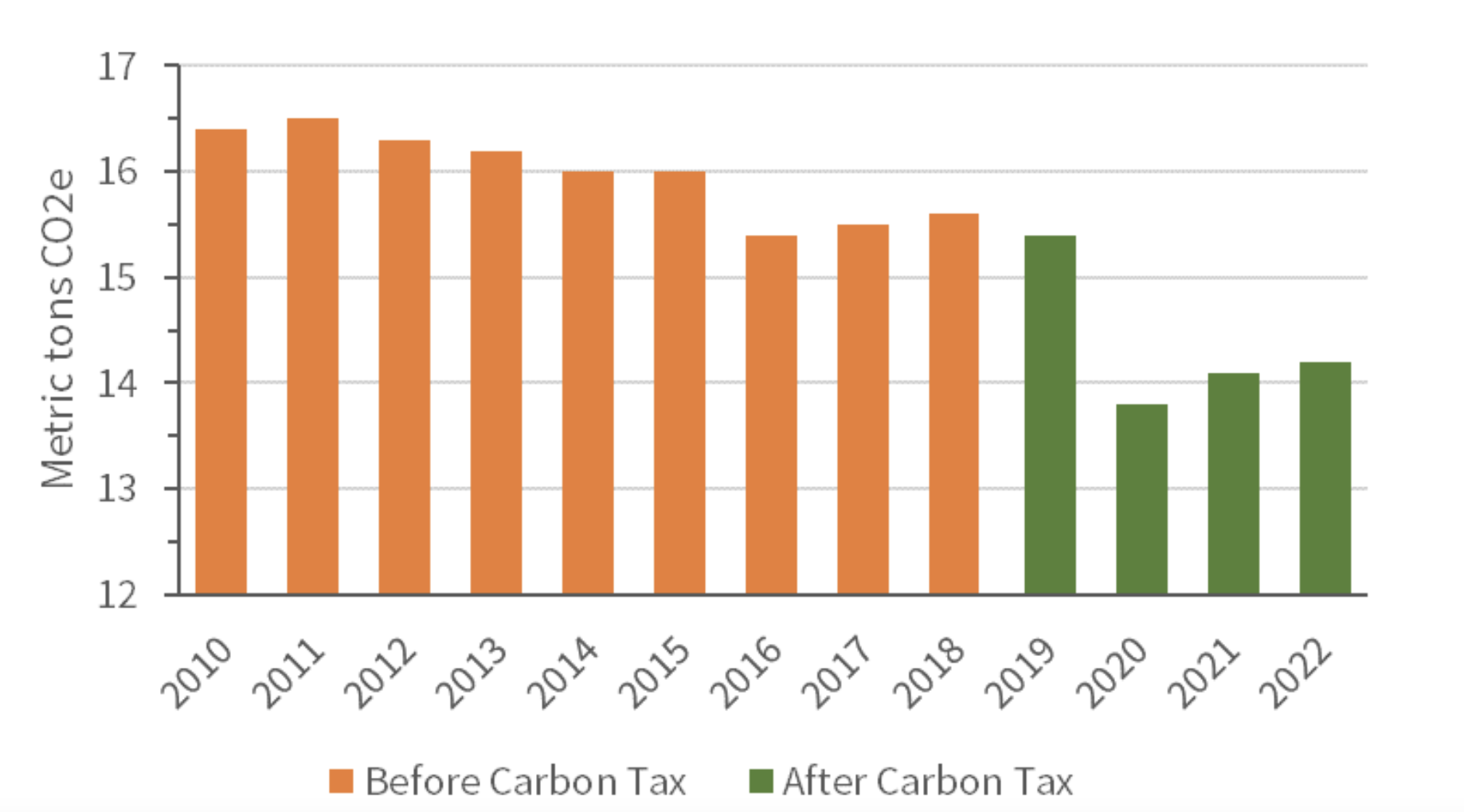

The emissions

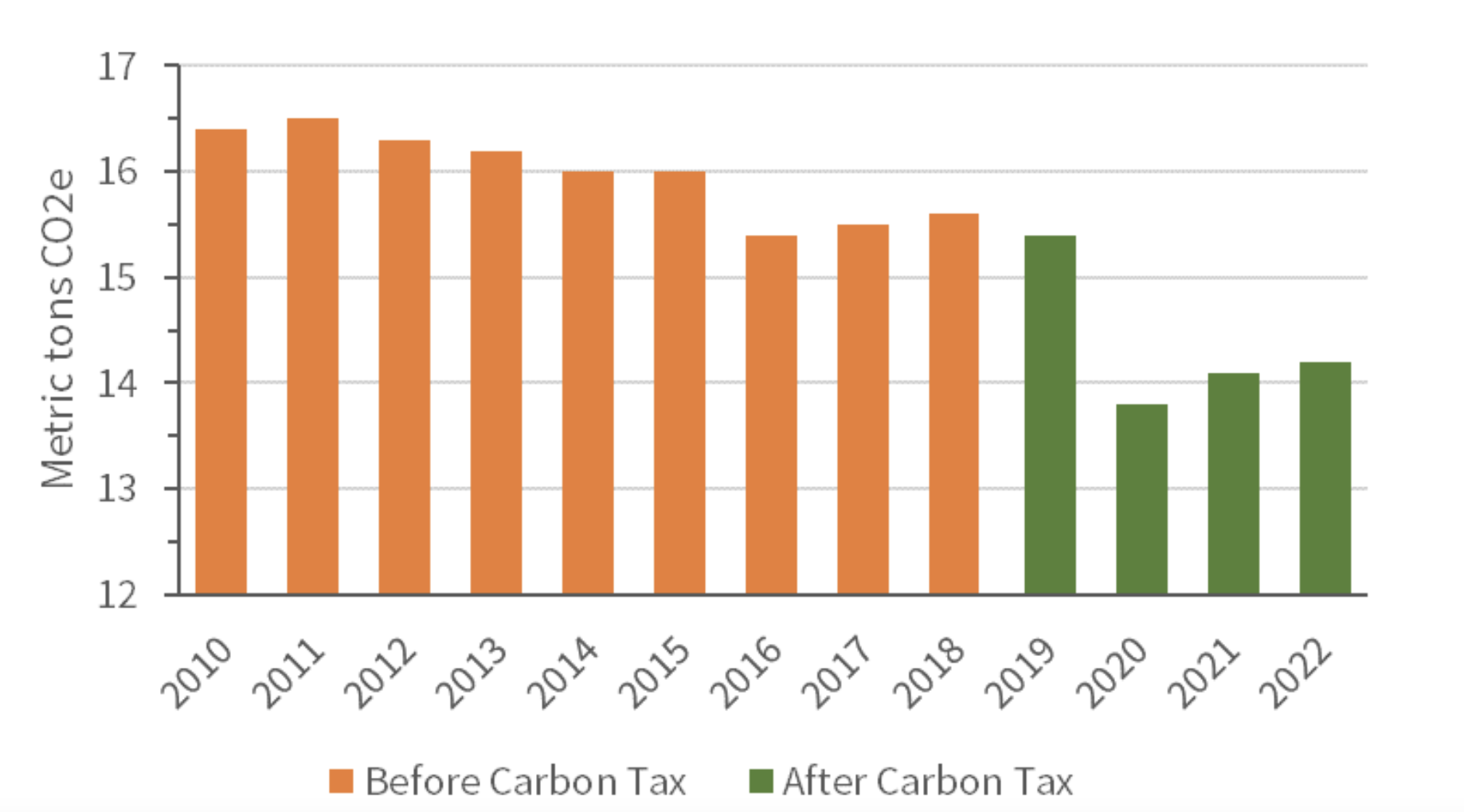

Here is a chart of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions per person from 2010 to 2022. The orange bars are prior to the enactment of the carbon tax, and the green bars are with the tax in effect.

Canadian Greenhouse Gas Emissions per Capita (Chart by CCL, adapted from Our World in Data)

Emissions clearly went down, but no reports have yet revealed how much of the decline is due to carbon pricing. Answering this question is complicated by the economic impact of the pandemic and, as this CTV article notes, “it’s not the only climate policy in Canada.” But it’s still clear that emissions are lower than they were before the carbon tax went into effect. Canadian author Michael Barnard explains that the decline is not chiefly due to individual day-to-day behavior, but longer-term decisions by businesses and consumers, such as replacing an old gas furnace with a heat pump or an old gasoline vehicle with an electric car.

So is opposition growing because the carbon tax imposes a net financial burden on average households?

Household costs

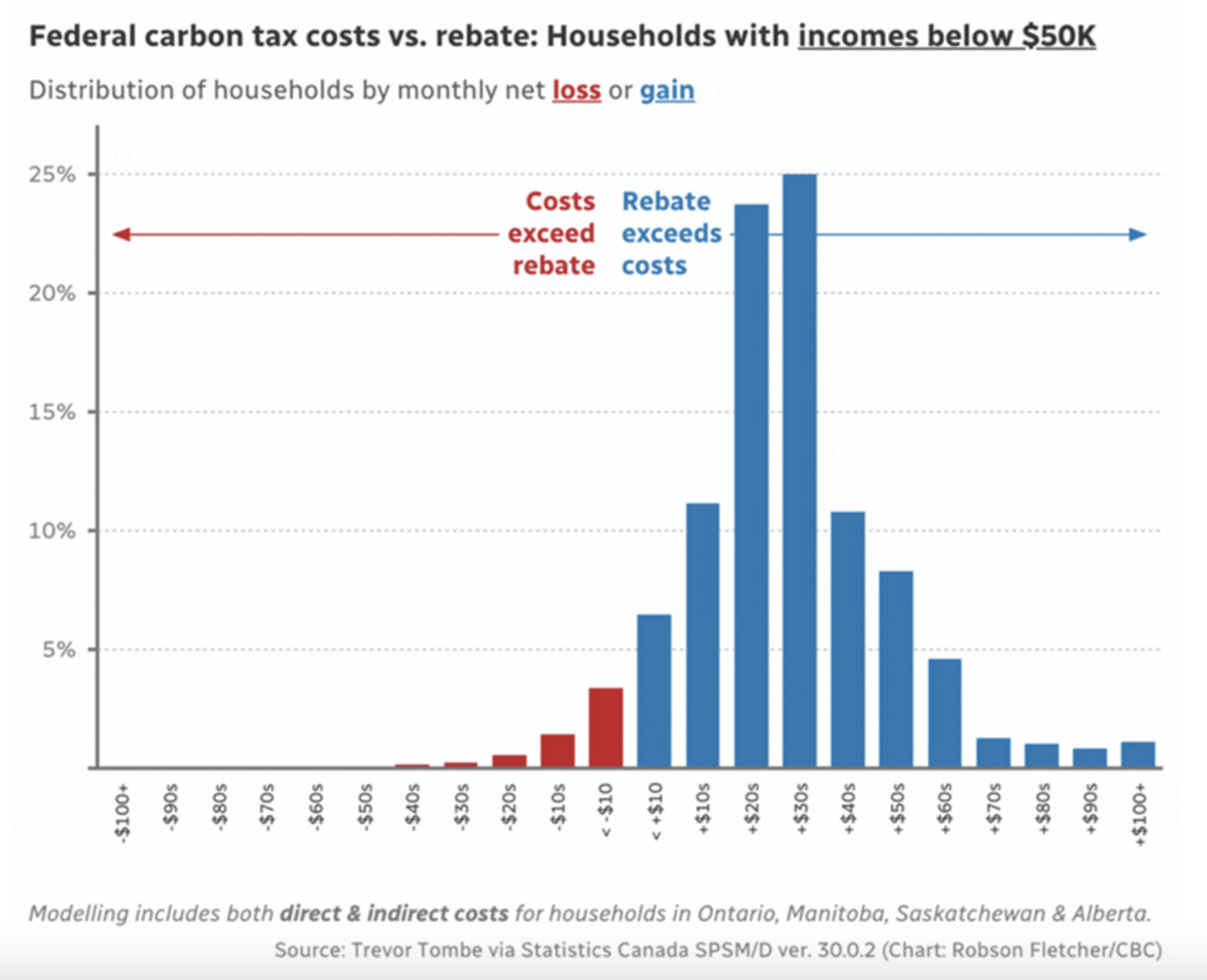

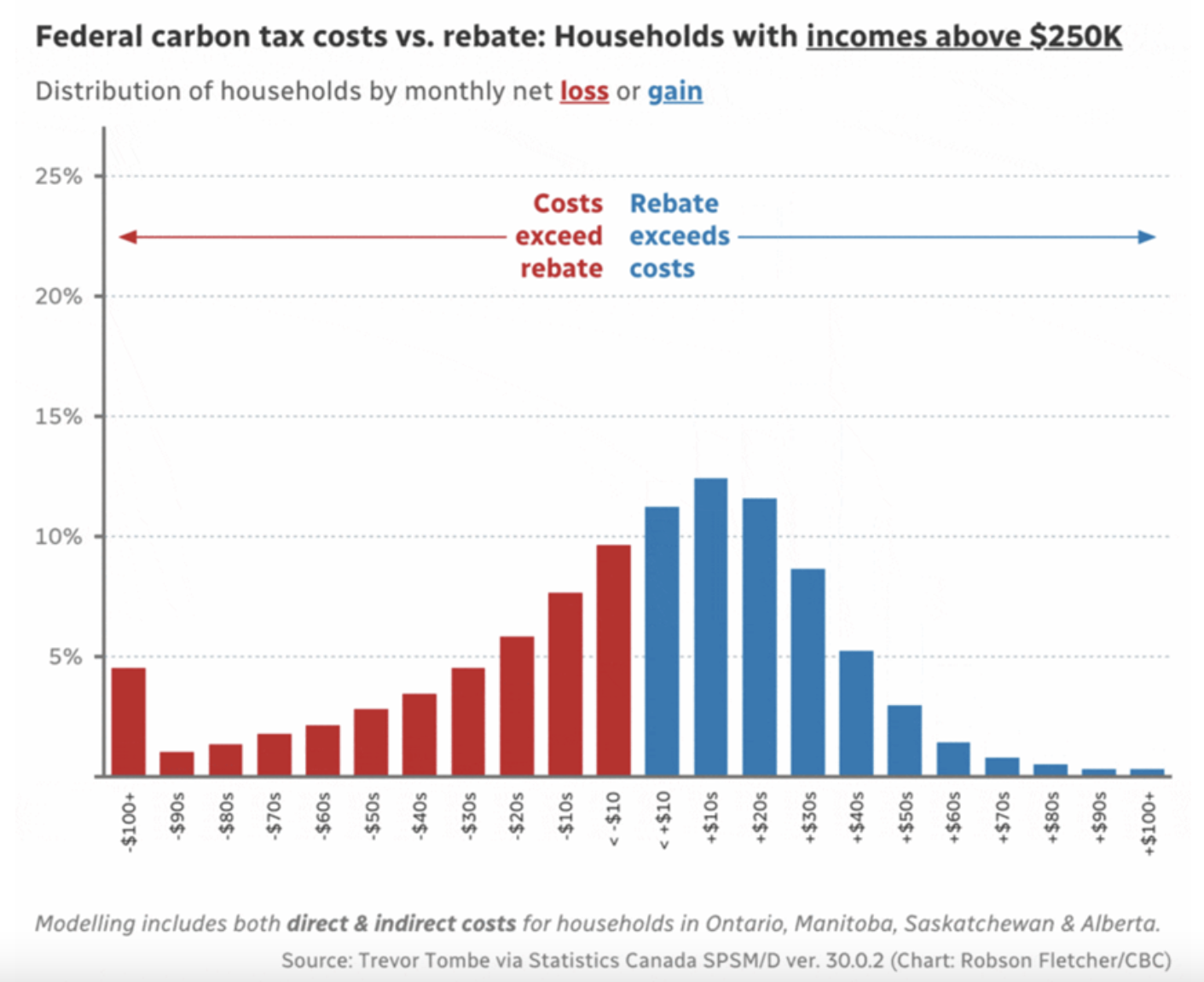

That doesn’t seem to be the case, according to this article that delves into the distributional impacts. The charts below are drawn from Statistics Canada’s Social Policy Simulation Database and Model and were reported by Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO). The top chart shows how rebates (blue) stack up versus energy costs (red) for the lowest-income households, and the bottom chart shows the same data for the highest-income segment of the population.

Costs vs rebates for lowest and highest income level (adapted from Robson Fletcher/CBC)

Among low-income households, 94% get more in rebates than their carbon tax costs, with more than half netting at least C$30 per month. Even for the high-income households, rebates still exceed costs for a healthy 55%. These results are strikingly similar to those estimated in CCL’s Household Impact Study of the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act.

And yet, Poilievre and his allies claim that “the carbon tax will cost most households more than they ever get back.” That claim is drawn from the same PBO report cited above, which on the one hand shows that wealthy households will bear a much higher portion of the cost for reducing emissions, but on the other hand says that all households will see reduced income growth due to suppressed economic activity.

So what’s going on here?

The economy

According to CBC analyst Peter Zimonjic, the PBO report does not consider “the cost to the economy of doing nothing about climate change, the economic growth that could result from a shift to a green economy, and how carbon pricing compares to other climate policies such as regulations or tax credits.”

There may be an even more fundamental problem with the PBO analysis. As Zimonjic notes, a 2020 NBER research paper showed that the type of modeling used by the PBO does not comport with real-world data from three decades of carbon pricing in 31 European countries. That study showed no suppression of economic activity due to carbon taxes. And to further underscore this, a 2021 CBO paper states that “sending each household an equal share [of carbon tax revenue] in the form of a rebate could more than offset the economic incidence … of the carbon tax.”

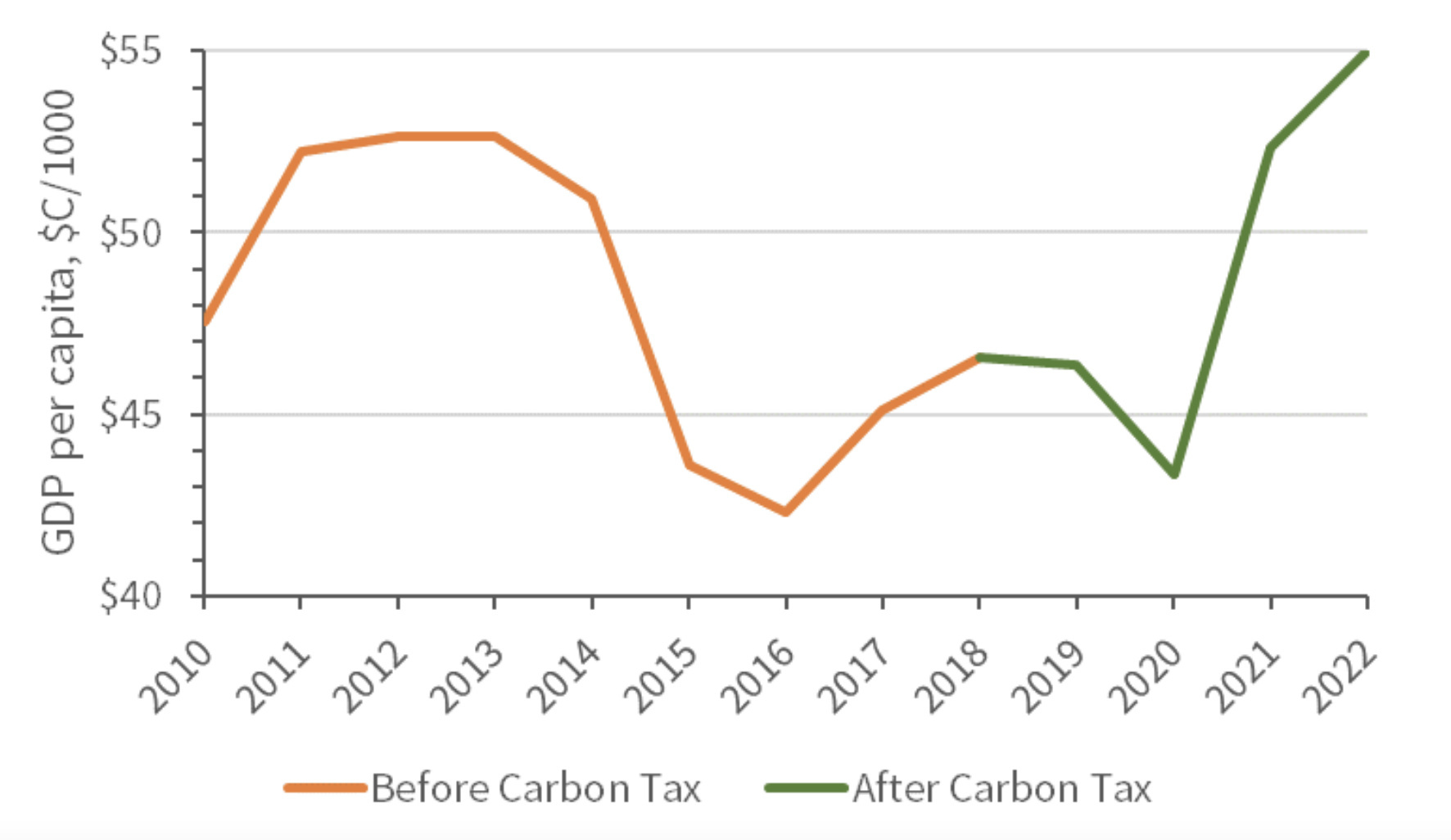

Here is Canadian GDP growth before and after the carbon tax was enacted.

Canadian GDP per capita(Chart by CCL based on data from World Bank)

From 2018 to 2022, Canada’s per-capita GDP grew from C$46.5K to C$55.0K, overcoming the pandemic recession and even blowing past its previous peak in 2013. Thus, real-world data throws some shade on Poilievre’s argument to “axe the tax.”

Unfortunately, though, voters don’t consult studies and charts before they go to the polls; they vote according to what they believe to be true. And that’s where public messaging is crucial.

The politics

There is a conventional wisdom in politics that taxes are always toxic. Canada defied that axiom when a coalition passed the carbon tax and maintained its popularity through the subsequent election cycle. But with another election approaching in 2025, the oppositional deluge has arrived. It seems to be working, despite the factual inaccuracy of anti-carbon price arguments. According to a government report for 2021, the average household rebate in the provinces where the federal tax applied exceeded the average carbon cost by C$249. But in a recent poll, only 14% of those polled believed their rebates exceeded their carbon tax costs, while 54% felt they came up short.

“What we’re learning in Canada is that our job as climate advocates is not over after a policy is enacted,” said Citizens’ Climate International Program Director Cathy Orlando, who’s been lobbying the Canadian Parliament since 2010. “Despite the fact that Climate Action Rebates are working for Canadian families and communities, the perception gap is putting this effective tool at risk. The effort to dismantle Canada’s carbon pricing policy is an effort to transfer wealth from ordinary Canadians to polluters. Our volunteers at Citizens Climate Lobby Canada will be working diligently this year and next to make sure the public knows the truth.”

This gulf between reality and perception shows that it’s not enough to simply tell the truth, nor is it enough to sell a policy product like a carbon tax once. The sale has to be made again and again until it becomes part of the sociopolitical landscape.

But black swan events like a pandemic can scramble public opinion in unpredictable ways, particularly when it affects the economy chaotically. Under COVID-19, supply chains ground to a halt, unemployment spiked, and then subsequent pent-up demand – exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – fueled inflation. Naturally, the opposition party grabbed the opportunity to assign blame to government policy – and to the carbon tax in particular.

This is a stark lesson in how seriously to take the political challenges around carbon pricing. Ironically, most people – Canadians and Americans alike – want their government to address climate change, but they can be easily turned against a policy that will actually work.

Can this conundrum be solved? A Financial Times article about the ups and downs of carbon pricing provides some guarded optimism, with one European economist noting that “Carbon pricing should go hand in hand with carbon dividends . . . Without carbon dividends, it is socially and politically unsustainable.”

Those of us who agree have the truth on our side. All we have to do is get people to understand it.