Novel new study offers hope for climate success and a key role for CCL

By Dana Nuccitelli, CCL Research Coordinator

Climate research can tend to be discouraging, with extreme weather impacts becoming increasingly severe and governments generally being too slow to act. But a recent study published in the journal Nature and led by University of California, Davis climate economist Frances Moore offers a glimmer of hope that we might successfully address the climate crisis. It also underscores why CCL volunteers should resist the temptation to let near-term setbacks or delays knock us off course. We need neither despair nor panic, but to remain persistent and focused.

In the past, almost all climate modeling studies have projected how Earth’s climate will change in response to a variety of greenhouse gas emissions pathways. What they haven’t done is try to predict how social and political factors will alter those future human emissions. That’s a challenging question to answer because societal behavior is difficult to predict, but it’s a critical one because human carbon pollution will be the single most important factor determining how much the climate continues to change over the coming decades.

A study of climate-social feedbacks

Moore’s team sought to answer this question by reviewing literature and talking with experts from a variety of disciplines including social and cognitive psychology, economics, sociology, law, political science, and energy systems engineering. They were looking for ways in which societal feedback processes influence policy changes. For example, public support can often translate into policy changes; policy changes can influence social norms and behaviors and also industry lobbying; the costs of new technologies can fall rapidly as they are deployed and benefit from the economies of scale and “learning by doing.” For more details about these feedbacks, see my article at Yale Climate Connections.

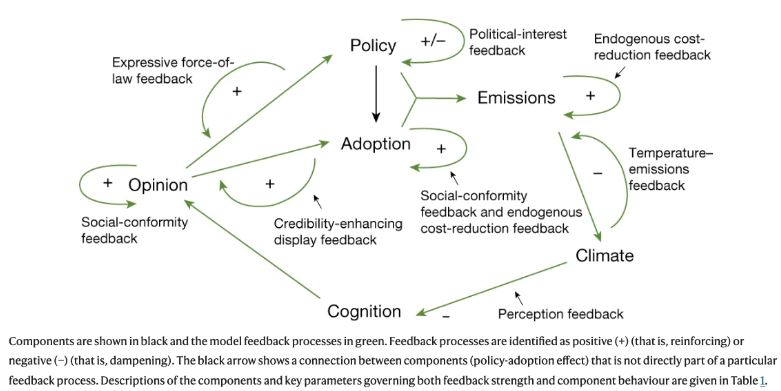

Moore’s team incorporated seven such climate-social feedback effects into their model (as illustrated in the diagram below) and ran 100,000 simulations to assess how these effects might trigger climate policy and emissions changes. They then grouped together model runs that had similar trajectories of climate policy and emissions through the end of the century.

A diagram illustrating how the seven climate-social feedbacks are incorporated into the model and their reinforcing (positive) or dampening (negative) effects. Source: Moore et al. (2022), Nature.

Hopeful results

The study’s results were encouraging. In the biggest cluster representing almost half of the model runs (called the “modal path”), global temperatures in 2100 were around 2.3°C hotter than pre-industrial temperatures. That’s a bit beyond the Paris agreement to limit global warming below 2°C, but incorporating carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere, which was not included in the model, would give this biggest group of model runs a shot at meeting the Paris targets.

The second-biggest cluster (called “aggressive action”) represented more than a quarter of model simulations. It fared even better, limiting global warming to less than 2°C even without including carbon dioxide removal efforts. The third-largest cluster (called “technical challenges”) represented almost one-fifth of the model runs. In this category, government climate policies are similar to those in the most common “modal path” group, but clean technologies remain relatively expensive in light of a weak “learning by doing” feedback, which would slow efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In this scenario, global temperatures rise by about 3°C (5.4°F) above pre-industrial temperatures in 2100.

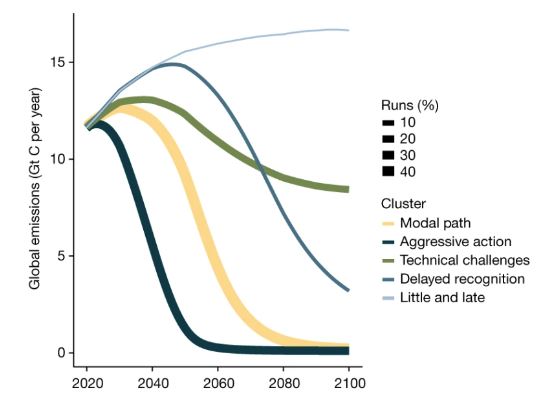

Together, these three scenarios account for nearly 95% of the model simulations, and they all envision many governments enacting climate policies well beyond the current status quo in an effort to meet Paris commitments. Two other tiny clusters labeled by the study authors as “delayed recognition” and “little and late” would incur about 3–3.5°C warming in 2100.

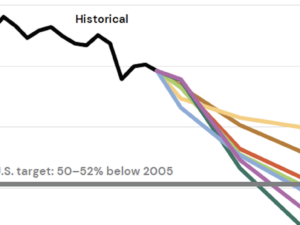

It’s also worth noting that in the big “modal path” cluster (yellow in the chart below), global carbon emissions continue to rise over the next eight years, missing international 2030 Paris commitments, but fall rapidly in the decades thereafter. This scenario envisions a cascade effect in which public support gradually spurs climate policies in many countries. That catalyzes the deployment of clean technologies, which drives down their costs, which further increases public support, and so on.

Global carbon emissions trajectories from 100,000 runs of the coupled climate–social model, grouped into five clusters. The line thickness corresponds to the size of the cluster. Source: Moore et al. (2022), Nature.

What role can CCL play?

I asked Moore how CCL’s grassroots advocacy would fit into the feedbacks modeled by her team. She told me,

“If I were to think about where grassroots activism most played a role in the model, it would be in the social-conformity feedback in the opinion component. This captures the role of these social movements in persuading larger fractions of the population of the importance of collective action through the political system.”

In short, CCL volunteers are a “persuasive force” that can convince other people to support climate policies. But CCL isn’t just any advocacy group; we also directly lobby members of Congress. Moore agreed that CCL’s lobbying efforts might help translate public opinion into climate policy by conveying that support directly to policymakers, although it’s not an effect included in her team’s model.

There are of course many uncertainties and caveats in the model and its results, and its outlook could be too rosy if some negative policy feedbacks are missing, for example. But the study at least offers hope that public support may spur cascading climate policies that will accelerate emissions cuts in the coming decades and bring the Paris targets within reach. And grassroots advocacy like CCL’s could play a key role in turning that simulated pathway into a reality.

Got questions or comments about this or any other climate research? Join the discussion with the Research Team at CCL’s brand new Nerd Corner!