(Image by Fibonnaci Blue)

What California’s experience demonstrates about the effect of carbon pricing on environmental justice

By Jonathan Marshall

Even before presidential candidate Joe Biden introduced his “Plan to Secure Environmental Justice and Equitable Opportunity in a Clean Energy Future,” growing numbers of Americans began seeing climate policy and environmental justice as intertwined issues. The environmental justice movement has focused overdue national attention on the disproportionate exposure to unhealthy pollution long faced by marginalized communities, among other issues.

Fortunately, strong climate policies that discourage the burning of fossil fuels will almost always help such disadvantaged populations, which are especially vulnerable both to the immediate health impacts of local air pollution and to growing threats created by extreme weather and other aspects of climate disruption. Carbon fee and dividend is strong medicine for both ills and a humane way to protect lower-income households from the costs of transitioning to a zero-carbon economy.

But some progressive activists, distrustful of market-based solutions, have accused California’s system of carbon pricing of simply shifting ongoing industrial pollution into marginalized neighborhoods. Fortunately, new research helps address at least some of those concerns and supports our advocacy of carbon fee and dividend as a national climate policy.

California’s “cap-and-trade” program, which kicked off in 2013, requires major greenhouse gas polluters (typically facilities emitting 25,000 or more metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year) to acquire permits, which they can buy and sell. The number of permits is slated to decline over time. The market for these permits determines a statewide price for emissions of carbon dioxide.

One controversial feature of California’s system is the ability of polluters to “offset” some of their emissions, and thus require fewer permits, by investing in out-of-state climate projects, such as forest protection. Critics have raised legitimate questions about the effectiveness and permanence of such offsets. Many environmental justice advocates also see them as a way to continue polluting inside the state at the expense of disadvantaged communities.

An oft-cited 2016 paper by several California-based scholars seemed to find that the state’s program indeed failed to discourage many of the worst greenhouse gas polluters from curbing their emissions. They claimed it thus allowed dangerous co-pollutants, such as fine particulates, to continue harming residents—particularly those in communities of color. But the paper failed to prove a cause-and-effect relationship between the cap-and-trade program and the conditions it described.

Since that paper was published, several economists have taken a deeper dive into the data. In particular, by examining control groups of unregulated facilities, they tease out which changes in the level and geographic composition of pollution were likely caused by the cap-and-trade program instead of unrelated economic trends. That’s the best way to infer whether an increase in air emissions in California was due to cap and trade or, for example, a drop in natural gas prices.

- A 2018 paper by University of Oregon economist Ryan Walch examined emissions data from virtually all power plants in the United States to gauge the effect of California’s specific policies. His findings pointed toward state reductions in harmful air pollutants with “no compelling evidence for adverse environmental justice impacts for co-pollutants in low-income or high-minority-share communities in California.”

- A 2019 paper by Kyle Meng, an environmental economist at the University of California, Santa Barbara compared emissions from all covered facilities in California by zip code. He reported that “If anything, the evidence suggests that disadvantaged communities may have experienced on average a greater decline in emissions since the start of the cap-and-trade program than other communities.”

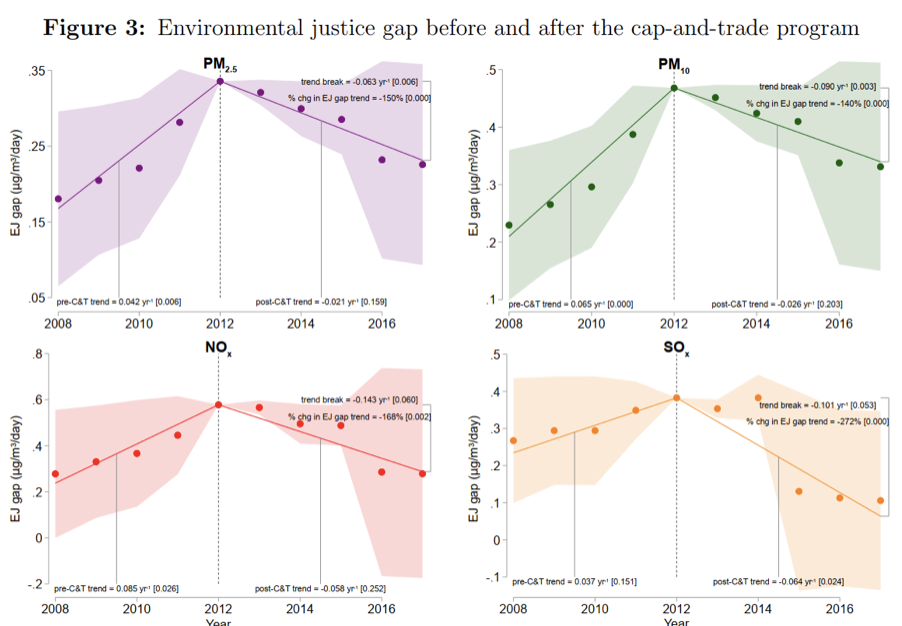

- A much more sophisticated 2022 paper by Meng and a colleague at Arizona State University found that over the years 2012 to 2017, California’s cap-and-trade program cut emissions of deadly particulates and smog-forming gasses from covered facilities by 15 to 45 percent. Just as strikingly, it showed that previously widening gaps between disadvantaged and other communities began narrowing as cap and trade drove down air emissions. Figure 3 of their paper, reproduced below, shows the sharp break in relative exposure to four air pollutants starting in 2013, after the program took effect.

The “EJ gap” displayed in the above charts denotes the excess exposure to air pollutants experienced by disadvantaged communities compared to other communities. In all four cases this gap, which had been steadily getting worse up to 2012, reversed direction and declined after California’s cap and trade program went into effect.

Looking ahead

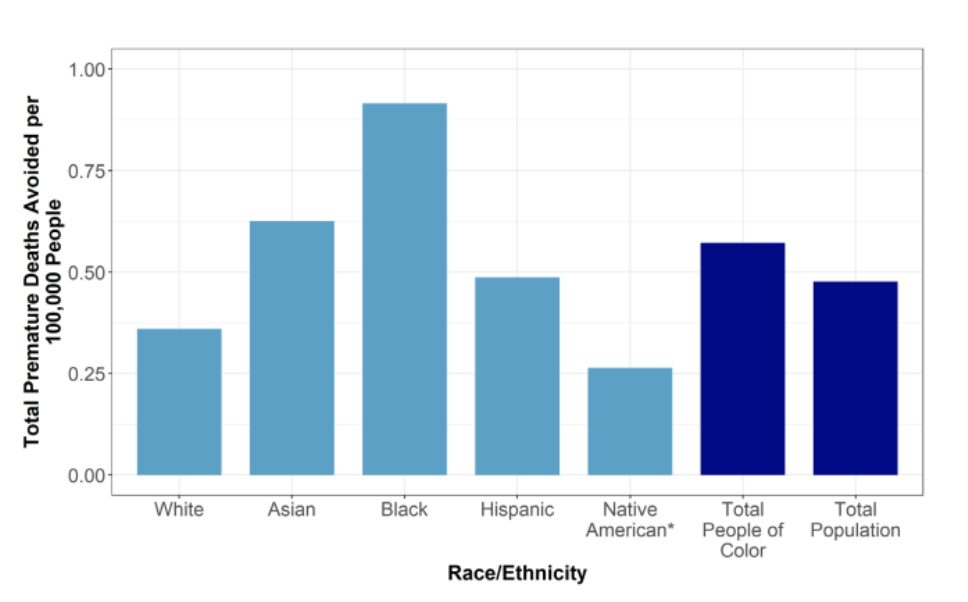

The California Environmental Protection Agency reported earlier this year that the state’s cap-and-trade program has saved significant numbers of lives—disproportionately in favor of people of color—by reducing exposure to fine particulate pollution (see chart below).

Population-Adjusted Premature Deaths Avoided with Change in PM2.5 Emissions from California Facilities Covered by Cap-and-Trade from 2012 to 2017 by Race/Ethnicity

Source: Zeise and Blumenfeld, “Impacts of Greenhouse Gas Emission Limits Within Disadvantaged Communities: Progress Toward Reducing Inequities,” CalEPA, 2022.

Nonetheless, many environmental justice activists legitimately complain that carbon prices in California remained far too low for many years to make a substantial dent in either carbon emissions or local co-pollutants. That’s an indictment of the program’s administration rather than carbon pricing itself. To avoid such problems, the state’s Environmental Justice Advisory Committee recommended in 2017 that cap-and-trade be replaced with a “system like a carbon tax or fee and dividend program.” That effort has so far failed, but California’s carbon price has risen and is now above $25 per metric ton of CO2 equivalent.

For all this good news about carbon pricing, no one argues that it represents a solution to all or even most environmental justice issues. Deep inequities continue to plague too many communities even in California and much work remains to be done to address them. Continued dialogue with members of frontline communities is essential and will lead to better policy.

Jonathan Marshall, the Economics Research Coordinator for Citizens’ Climate Education, is former Economics Editor of the San Francisco Chronicle and the author of six books.