By Dana Nuccitelli

A new study published in Nature Climate Change made some waves with its assertion that dividends do not increase the popularity of a carbon price. The reason — somewhat buried in the paper and associated stories from the Atlantic and David Roberts’ Volts newsletter— is that citizens in countries with carbon fee and rebate systems tend to overestimate their carbon costs. The paper notes of carbon fee and dividend in Canada:

“The policy is highly progressive, with 80% of households receiving more in dividends than they pay in carbon taxes … Canadians who learned the true value of their rebates were significantly more likely to perceive themselves as net losers even though most Canadians are net beneficiaries.”

There’s an important lesson to be learned here — it’s not enough to provide carbon cashbacks that exceed the carbon fee costs. If you only take one thing away from this study, make it this: dividends must be coupled with educational efforts to inform citizens about how much the carbon price is increasing their costs and that the carbon fee and dividend system is generating a net income for most households. We can show people the size of their dividends on checks, but individuals’ carbon fee costs are much tougher to add up, and this study indicates people may tend to overestimate them.

With that key takeaway highlighted, let’s dig deeper into this paper.

Learn more about carbon cashback

What did the study do?

The paper looked at the two countries that have carbon fee and rebate systems in place today. Canada is the most relevant example, with a carbon price whose revenue is currently rebated via an income tax credit. Switzerland returns its carbon tax revenue through a discount on health insurance premiums.

These are rather opaque ways to provide dividends to households. (Canada will begin mailing dividend checks to households this July, and the study authors will then gather more data.) Unsurprisingly then, the study found that citizens are poorly informed about the rebates. Specifically, 25% of residents in Saskatchewan and 45% in Ontario did not even know they had received a rebate, and on average individuals underestimated the size of their dividends by 40% and 32%, respectively. Only 12% of Swiss respondents knew that carbon tax revenues were redistributed to the public at all.

The study authors took advantage of this lack of information to conduct an experiment. They performed a survey in which half of participants were informed about the size of their carbon rebates. Survey participants in this experimental group answered much more accurately when asked about the size of their rebates. Education works!

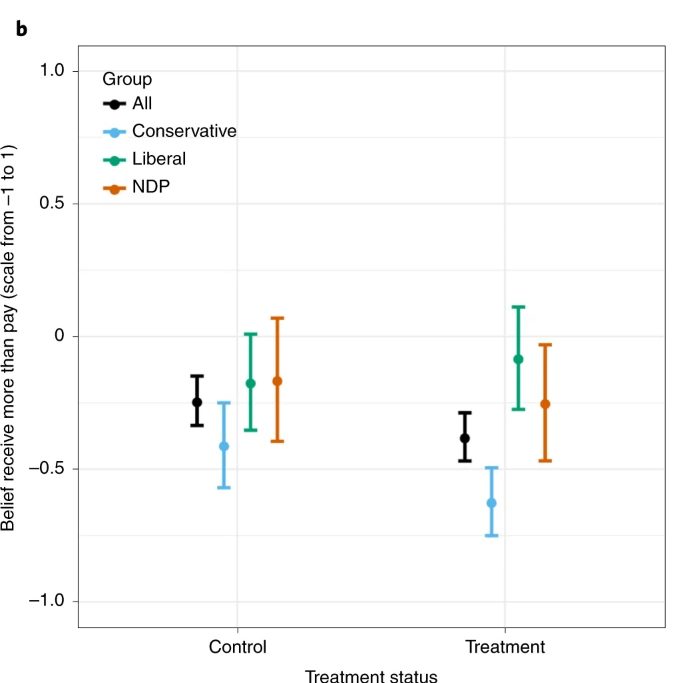

But the experiment did not include any information about the participants’ increased carbon costs, and as noted above, most Canadians incorrectly believed that the rebates were insufficient to cover those costs. As a result, receiving information about the size of the rebate actually decreased support for the fee and dividend system among members of the Canadian Conservative Party due to an overestimation of their carbon costs.

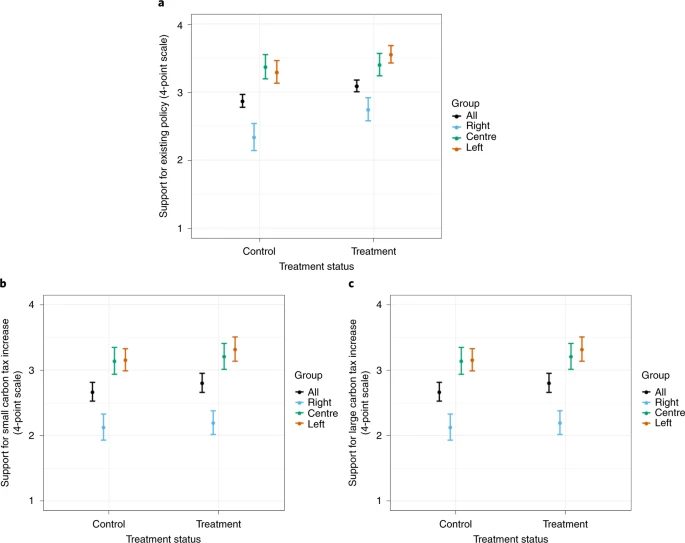

In Switzerland, where the carbon fee revenue was distributed in the form of reduced health insurance premiums, the rebate information slightly increased citizens’ already strong support for the country’s carbon fee. However, it did not significantly increase support for raising the carbon price — a proposition that was narrowly defeated in a national referendum last summer. Switzerland’s current carbon price ($105 per ton, rising to about $130 this year) is nevertheless already one of the highest in the world.

Carbon fee and dividend is already popular

Another key take-home point from this study is that while the dividend information did not increase support for carbon pricing in Canada or have very much effect on support in Switzerland, the policy is already broadly popular.

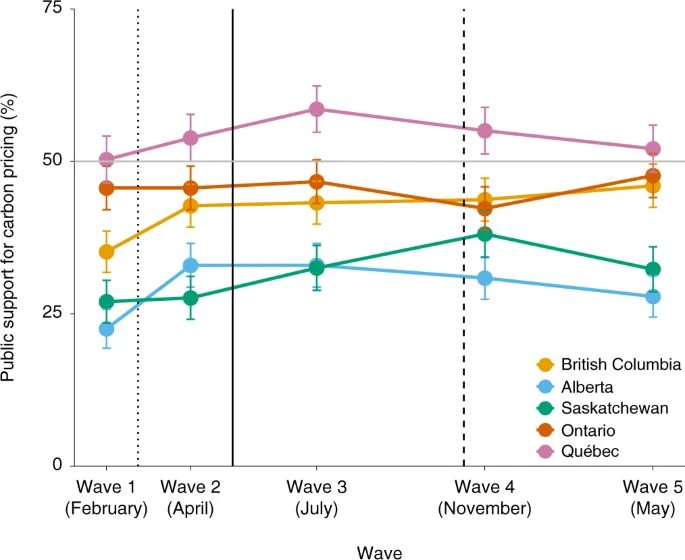

The study survey found that Swiss support for their existing carbon price averaged about a 3 out of a 4-point scale. Canadians are evenly split in their support and opposition to the country’s carbon fee and dividend, but Justin Trudeau has remained Prime Minister in the two elections held since the carbon fee was enacted, including a recent election held after his government announced that the carbon price will rise to $170 per ton by 2030.

Perhaps most tellingly, the Canadian Conservative Party now includes a smaller carbon fee and dividend plan in its own platform. They view opposing the policy as a losing political position, and Conservative voters have a net positive view (+17%) of their party’s new carbon fee and dividend platform.

In surveys of American voters, close to 70% support a revenue-neutral carbon price, including nearly half of Republicans. Simply put, carbon fee and dividend is already a pretty popular policy. But public support isn’t the only requirement for a policy to become law. For example, the vast majority of Americans across the political spectrum have long supported universal gun background checks, and yet no such law has been passed. Policy popularity is important, but it isn’t the only thing that matters.

Carbon cashbacks are smart policy

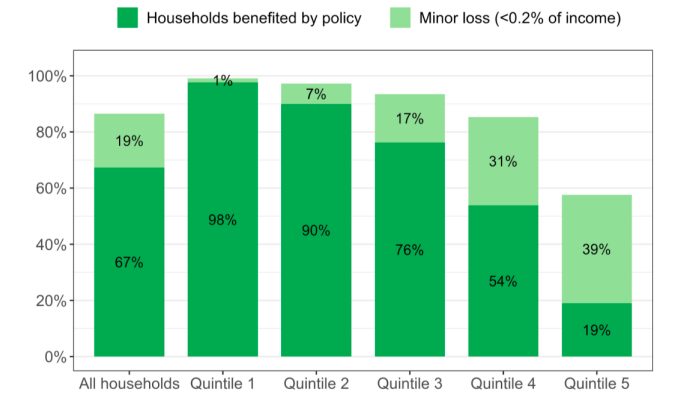

Increasing the popularity of a carbon price isn’t the only (or even the most important) reason why dividends are good policy. If we make polluters pay for their carbon pollution, they will pass those costs along to consumers, and low-income households spend the largest proportion of their income on energy costs. Without dividends, carbon pricing tackles the climate crisis on the backs of low-income Americans. CCL does not consider that an acceptable approach.

On the other hand, as the Household Impact Study illustrated, sending carbon cashbacks equally to taxpayers generates a net income for nearly all low-income households because they have relatively small carbon footprints.

Percent of American households receiving a net income (dark green) or minor net loss (light green) by income quintile from the poorest 20% to the wealthiest 20% of households, from the 2020 Household Impact Study. 98% of lowest-income households come out ahead from carbon fee and dividend.

A Nov. 2021 study in Nature Climate Change also estimated that a $50 per ton carbon fee and dividend would lift 1.6 million Americans out of poverty. And a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that monthly dividends provided to low-income families changed children’s experiences and increased their brain activity, which “has been associated with the development of subsequent cognitive skills.”

In other words, carbon cashbacks can alleviate poverty and give children in low-income households a better chance to succeed in life while simultaneously helping to preserve a stable climate for their future. It’s just good policy.

Partisanship is a problem. CCL is working on it.

Most of the coverage of the new study has focused on political partisanship because carbon fee and dividend support remained lower among conservatives even when survey participants were educated about their rebates. But partisanship colors support all climate policies. Some folks believed the Clean Electricity Performance Program (CEPP) would be more politically palatable than carbon fee and dividend, but the former was nixed last October while the latter still remains in the mix of possible policies with at least 49 Senate votes supporting its inclusion in Build Back Better more than three months later.

As the CCL communications team said, “It seems that partisanship is a big factor in whether people like the policy or not. That’s part of why CCL works in a bipartisan way to build support all across the political spectrum.” We’re also working hard to educate the public about the benefits of climate policies like carbon fee and dividend. As noted above, education works; another new study found that a brief exposure to pertinent facts increased Irish support for their country’s carbon price.

In short, carbon fee and dividend remains one of the single most effective climate policies, and CCL will continue to work on educational efforts with people of all political persuasions to carry it and other smart climate policies across the finish line.

Learn more about carbon cashback

Dana Nuccitelli is an environmental scientist and climate journalist with a Master’s Degree in physics. He has written about climate change since 2010 for Skeptical Science, for The Guardian from 2013 to 2018, and since 2018 for Yale Climate Connections. In 2015 he published the book “Climatology versus Pseudoscience”, and he has also authored ten peer-reviewed climate studies, including a 2013 paper that found a 97% consensus among peer-reviewed climate science research that humans are the primary cause of global warming.