Per Espen Stoknes giving his TED Talk titled “How to transform apocalypse fatigue into action on global warming.”

Use psychology for better climate communications

By Sara Wanous

Each month, Citizens’ Climate Lobby hosts an online meeting featuring a guest speaker to educate listeners on topics related to climate change, carbon fee and dividend, and the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act. Check out recaps of past speakers here.

We know that climate change is an urgent issue that requires action today, but engaging people in climate action remains a challenge. How do we use what we know about the human psyche to encourage action on climate change? Per Espen Stoknes examines this problem in his career as a psychologist and Norwegian Green Party Politician. From his November 2017 TED Talk to his book “What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming,” Per weaves together psychology and economics to examine the human relationship to the natural world and to each other. He joined our December 2018 meeting to share his perspective. You can watch the full meeting here or read our recap below.

Current climate communications

For the past nearly 30 years, climate change communications have taken two main approaches: information and doom.

Scientists and science-minded people have taken to pushing out facts, like how atmospheric CO2 emissions have changed over time or our remaining carbon budget to reach the 2 degree target. This approach is based in the assumption of an information deficit. In other words, we assume that people aren’t acting because they don’t have the right information or enough of it. We think, “If we provide the information, of course they’ll get engaged!”

Others have employed the “doom” approach of documenting the disastrous effects of climate change from devastating wildfires and floods to killer storms and droughts and how they’ll worsen with climate change. This approach assumes that putting the negative consequences of inaction into perspective will inspire action today.

However well intended these approaches may be, we see today that beating these same two drums isn’t effectively engaging more people in climate solutions. So why don’t the informational and doom approaches reach more people? And what are some more effective communication strategies?

Psychological barriers

Per Espen Stoknes advises that it isn’t that these approaches are wrong, it’s that they are insufficient. The information about climate risks and solutions are there, but psychological barriers preventing more people from getting engaged. Stoknes says, “The greatest barrier to solving climate change is about six inches thick: it’s the space between our ears.”

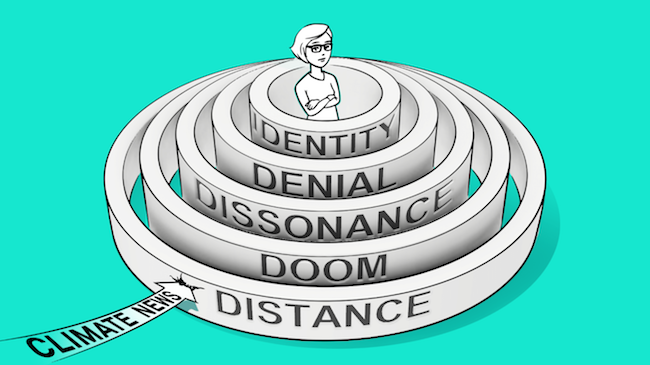

Visualization of the barriers to climate communications.

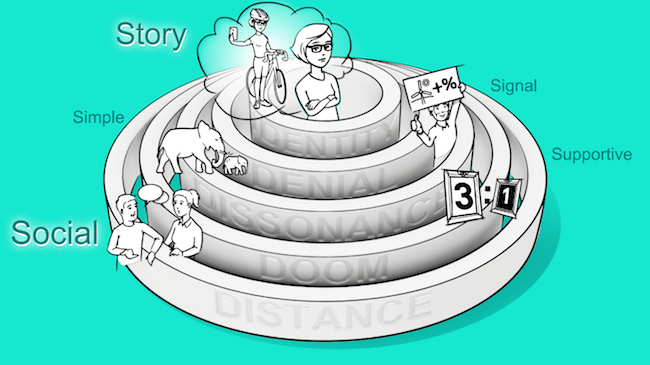

Barriers and effective approaches

Through his research, Per has found five barriers that prevent climate news from our current model from sinking in, and effective strategies to overcome each:

Barrier 1: Distance

The negative effects of climate change can often seem distant. The targets are far in the future, like our 2100 Paris Agreement goals; distant in space, like glaciers, polar bears, or coral reefs; or distant from some people’s daily lives, like the disproportionate effect of climate on poor people. Solutions seem distant as well because one person alone can’t make the big changes we need. With all of this distance, it’s psychologically easier to focus on nearer things, like your family or your career.

Effective Strategy: Social

Per explains that at our core, we are social creatures. We care about what our friends, neighbors, and colleagues are doing more than we what a scientist or a policy wonk advises. A positive environmental example of the social strategy are rooftop solar panels. Per explains, “This is not just electricity, it’s social. The new energy system is here. We flip the distance barrier by showing what our neighbors are doing.”

Barrier 2: Doom

Per shared that according to a study by the Oxford Institute of Journalism, “more than 80% of all climate news had employed the disaster frame.” Overusing the disaster frame can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and despondency that disengage people from climate news.

Effective Strategy: Support

When speaking about climate change, Per recommends using the “3:1” rule: three supportive framings for every one threat. You don’t have to omit the threats of climate change, but by pairing them with the benefits of taking action, like healthier meat alternatives and green jobs, you can make people associate climate change with positive solutions more than with doom.

Visualization of approaches to overcoming psychological barriers on climate change.

Barrier 3: Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is a psychological term for the internal conflict one experiences when confronted with new information that clashes with their current experience or world view. This conflict is uncomfortable, so we resolve the discomfort with self-justifications to ease psychological stress. For example, “I know it doesn’t help climate change to drive a car that uses gasoline, but my neighbor has a much bigger car, so I don’t feel too bad.”

Effective Strategy: Simplicity

The cognitive dissonance around climate change arises from learning of the problem but living in a world that is often structured in an unsustainable way. If we adjust consumer choices so that it’s the default to make climate friendly choices, we can relieve some of this dissonance. For example, if it’s more affordable and practical for people to choose an electric car rather than a gas car, they’ll do it.

Barrier 4: Denial

Denial in the psychological sense means having knowledge but living as if we don’t. Denial is a common coping method for cognitive dissonance. For example, if a person learns of all of the impacts their daily choices and actions have on the environment, it may be psychologically easier for them to deny that the problem exists than to manage the guilt of their actions and take steps to change their lifestyle.

Effective Strategy: Signal

“Gigatons of CO2” isn’t a meaningful metric for most people. Tracking environmental progress in a real way, like with apps that let you log environmental actions and tell you how many carbon emissions you’ve saved, or government reports on progress, can help maintain people’s motivation.

Barrier 5: Identity

If taking action on climate conflicts with a pre-existing identity that someone holds, they are more likely to reject climate action than go against their identity. For example, most calls to climate action are done in a way that include a larger government and more intervention and regulation. For someone who identifies as conservative, these may conflict with their identity that values smaller government. In this case, they are likely to employ “confirmation bias,” or filter out news that conflicts with their values or sense of self-identity. According to Per, “Identity trumps truth any day.”

Effective Strategy: Story

According to Per, climate communications can benefit from more personal, non-polarizing stories that focus on a positive future. These stories start from imagining a what a better, lower emissions society looks like, and celebrating the stories of people that are living that story. By telling these stories, we can help people see how their identity fits into a future that is acting on climate change.

Climate change is an important problem and the information and solutions we need are there, but we need engagement across political aisles and a across the world to make these solutions work. These strategies that Per Epsen Stoknes refined can help climate scientists and activists engage broader audiences in climate action.

To hear more from former Per Epsen Stoknes, including some Q&A with CCL volunteers, watch the entire December meeting on YouTube or listen to the podcast.

Sara Wanous has been the Membership Coordinator at Citizens’ Climate Lobby since January 2018. She has a B.A. in Economics and B.S. in Environmental Science and Policy from Chapman University and is pursuing a masters in Climate Science and Policy at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.