How to make carbon pricing more popular

By Jonathan Marshall, Economics Research Coordinator

You’d think supporters of a climate policy endorsed by more than 3,600 U.S. economists, the UN Secretary General, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, to name a few, would be riding high. Instead, many supporters of carbon pricing are on the defensive against skeptics who claim it can never work in America.

“The politics of tax-centered climate policy are hopeless,” declared New York Times columnist Paul Krugman in 2022. “This may be the optimal economic policy for reducing carbon pollution, but as the centerpiece of climate reforms, it has proven a political disaster,” asserted two political scientists in 2020. That view has become conventional wisdom among many journalists as well. It also helps explain why architects of the original Build Back Better proposal didn’t include carbon pricing.

The skeptics would seem to have a case. Broad new taxes are rarely popular, particularly when supporters can promise only uncertain benefits sometime in the future. The failure of the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill in the U.S. Senate in 2009, the failure of ballot initiatives in Washington state in 2016 and 2018, and the “Yellow Vest” protests against higher fuel taxes in France in 2018 all set back the global movement for carbon pricing.

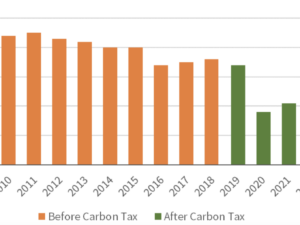

But to call the cause of carbon pricing “hopeless” seems premature when a record 68 such programs covered 23% of all global emissions in 2022, according to the latest World Bank report. At the start of 2023, Washington state bounced back from its previous setbacks and began implementing a new “cap-and-invest” carbon pricing system to help slash emissions. Let’s not forget, moreover, that a rising carbon tax reportedly came within one vote of being included in the budget reconciliation bill later known as the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

Studies of public attitudes toward climate policy

If carbon pricing is worth doing, and experience proves it’s possible, how can we raise the odds of implementing it? Many studies by political scientists, economists, and other behavioral scientists shed light on just that question, although they have received little attention in mainstream media or political commentary. Together, however, they provide clear signals on how to make carbon pricing politically viable.

The central insight from this literature is that “carbon pricing” comes in many different forms with equally many degrees of popular support. Finding the right political formula to address voter concerns without sacrificing effectiveness is the key–and it’s doable.

Political obstacles to carbon pricing

So what makes carbon pricing such a hard sell, besides the general aversion of voters to pay higher costs for fuel, utility bills, and the like? Here are the biggest issues identified by survey researchers:

Perceptions of unfairness. Many members of the public worry about the fairness of carbon pricing — both to their own pocketbooks and to those less fortunate. That concern was a prime motivator of the 2018 French revolt over higher fuel taxes, which was triggered in part by the government’s simultaneous cancellation of a wealth tax.

Public trust. Time and again, studies show a key obstacle is the lack of public trust. Many people believe politicians will take the revenue from a carbon tax and squander it rather than do anything to improve the environment.

Climate effectiveness. Closely related to the problem of trust is public ignorance about the climate effectiveness of carbon pricing. The power of a carbon tax doesn’t come primarily from the revenue it raises, but from the price incentives it creates for every consumer and producer to purchase and provide lower-carbon goods and services. Failing to understand this notion, many people suspect that carbon taxes are just an excuse to raise more revenue.

How to boost the popularity of carbon pricing

Fortunately, much of the recent literature on public attitudes toward climate policy explores ways to increase popular support for carbon pricing. The single most important finding is that how carbon revenues are spent makes a huge difference:

- Public distrust over government misuse of revenue can be eased by earmarking revenues, either by rebating them as revenue-neutral, lump-sum “dividends” (also called “carbon cashback”) to individuals or by spending it on environmental and climate programs.

- Public concern about the unfair impact of carbon pricing on people with fewer means can also be alleviated by earmarking revenue for low-income households or for dividends that have a progressive impact on such households.

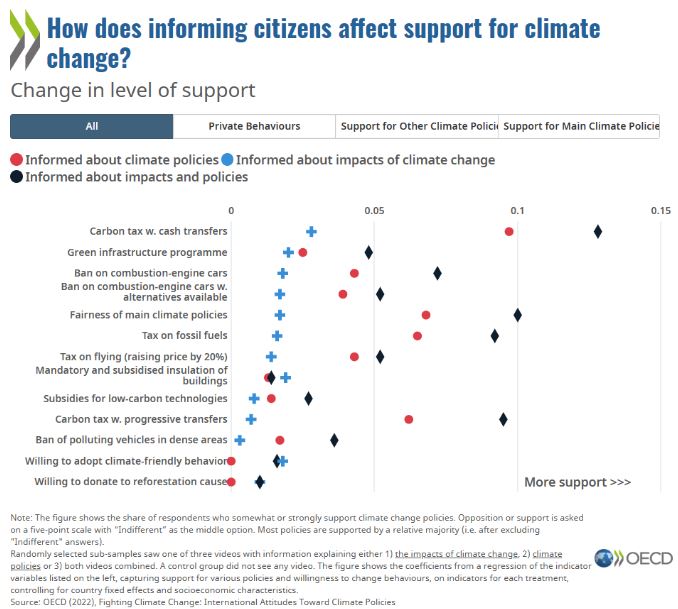

- Combining a carbon fee and dividend policy with public education to overcome public ignorance about its environmental and pocketbook effects is a winning strategy. Even a few minutes of explanation can grow public support substantially. One recent study found that providing people with basic estimates of the cost and dividend from a $50 carbon fee and dividend boosted support among Americans surveyed from 58% to 70%. Another recent study of more than 40,000 people in 20 countries showed that exposure to a five-minute video on carbon tax and dividends boosted support for the policy by nearly ten percentage points.

A few other findings to guide climate activists

- Terminology and labeling really do matter. People respond more positively to the concept of a carbon “fee” or “climate contribution” rather than a carbon “tax.” Bear in mind, of course, that opponents will work hard to impose their own, more negative labels and framing.

- One way to overcome public reluctance to accept new taxes is to start the carbon price low and then raise it over time. As one 2018 study observed, “A slow ramp-up, or even a trial period, provides individuals with the opportunity to gauge the costs and benefits of the tax. Taxes can then be raised progressively until they reach the level required to meet the environmental objective.”

- Governments that introduce early-stage programs need to make sure the benefits are highly salient. As one Canadian columnist complained about his own country’s otherwise cutting-edge carbon fee and dividend policy, “the best ideas in the world can fail if they’re not sold properly. . . All wonkish academic endorsements in the world won’t mean anything if voters don’t understand why you’re doing something and how it benefits them personally.” He was referring to the practice of issuing rebates as relatively invisible bank transfers or tax credits rather than well-publicized dividend checks.

- Politicians need to consider the public’s economic circumstances with empathy. “Governments must carefully manage the transition to higher carbon prices, in particular where taxes interact with volatile commodity prices,” wrote Adair Turner, former chair of the UK’s Financial Services Authority, soon after the rise of France’s Yellow Vest protests in 2018. “Intended increases should be gradual and declared far in advance, and they should be delayed when oil prices and thus pre-tax fuel costs are sharply increasing.” His words were certainly relevant to the political environment of 2022, when persistent and painful energy price spikes followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

These are not revolutionary ideas. Indeed, many of them have been incorporated into carbon fee-and-dividend proposals such as the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act, which attracted 95 co-sponsors in the 117th Congress. Still, it’s as helpful and reassuring to see which of one’s intuitions are supported by careful research as it is to see which others are off the mark. For carbon pricing advocates who want a deeper dive into the literature, check out CCL’s detailed new research guide, “Building Support for Carbon Pricing.”

Learn more about our solutions to climate change: