New report: How to cut emissions without deepening debt

By Jonathan Marshall

Champions of fiscal responsibility have had about as much success in recent years as climate activists, with the national debt and carbon buildup in the atmosphere both soaring. Now a prominent Washington-based organization has found a way to marry the two causes in a report praising the revenue-raising potential of federal carbon taxes, along with their environmental benefits.

First, let’s take a look at who wrote the report. It was issued Thursday by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB). The CRFB is a non-partisan, non-profit group led by a stellar list of political and business notables from both sides of the aisle, and it has street cred with many traditional conservatives. Its board includes former budget chiefs from the Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush administrations, a top domestic policy adviser to President George H. W. Bush, and the hard-nosed fiscal conservative Alan Simpson, who served as a senator from Wyoming for 18 years.

Titled “Can a Carbon Tax Fund Climate Investments?” the report analyzes the environmental and budgetary impacts of several plausible climate policy scenarios, including a revival of the climate provisions of the House-passed Build Back Better (BBB) bill, and carbon taxes of $20 per ton and $40 per ton (each growing just a bit per year).

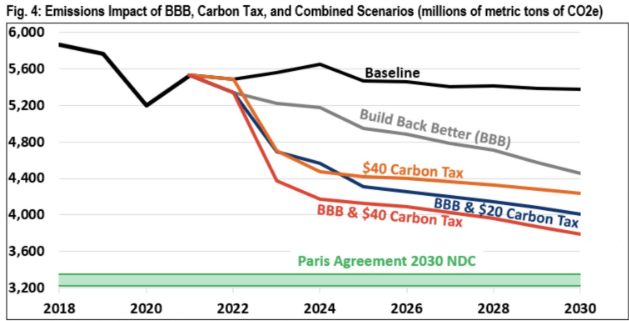

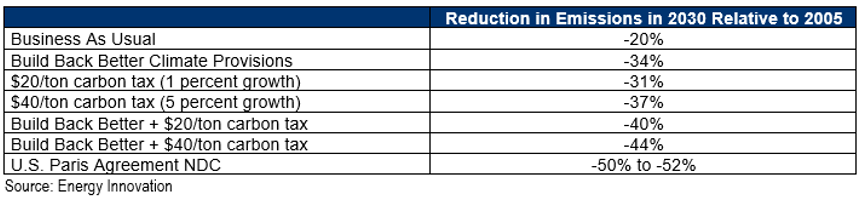

In particular, it compared projected emissions of carbon dioxide by 2030 under each policy with peak levels of just over 6 billion tons in 2005. America’s Paris pledge commits the United States to rolling back emissions to about 3 billion tons per year by 2030.

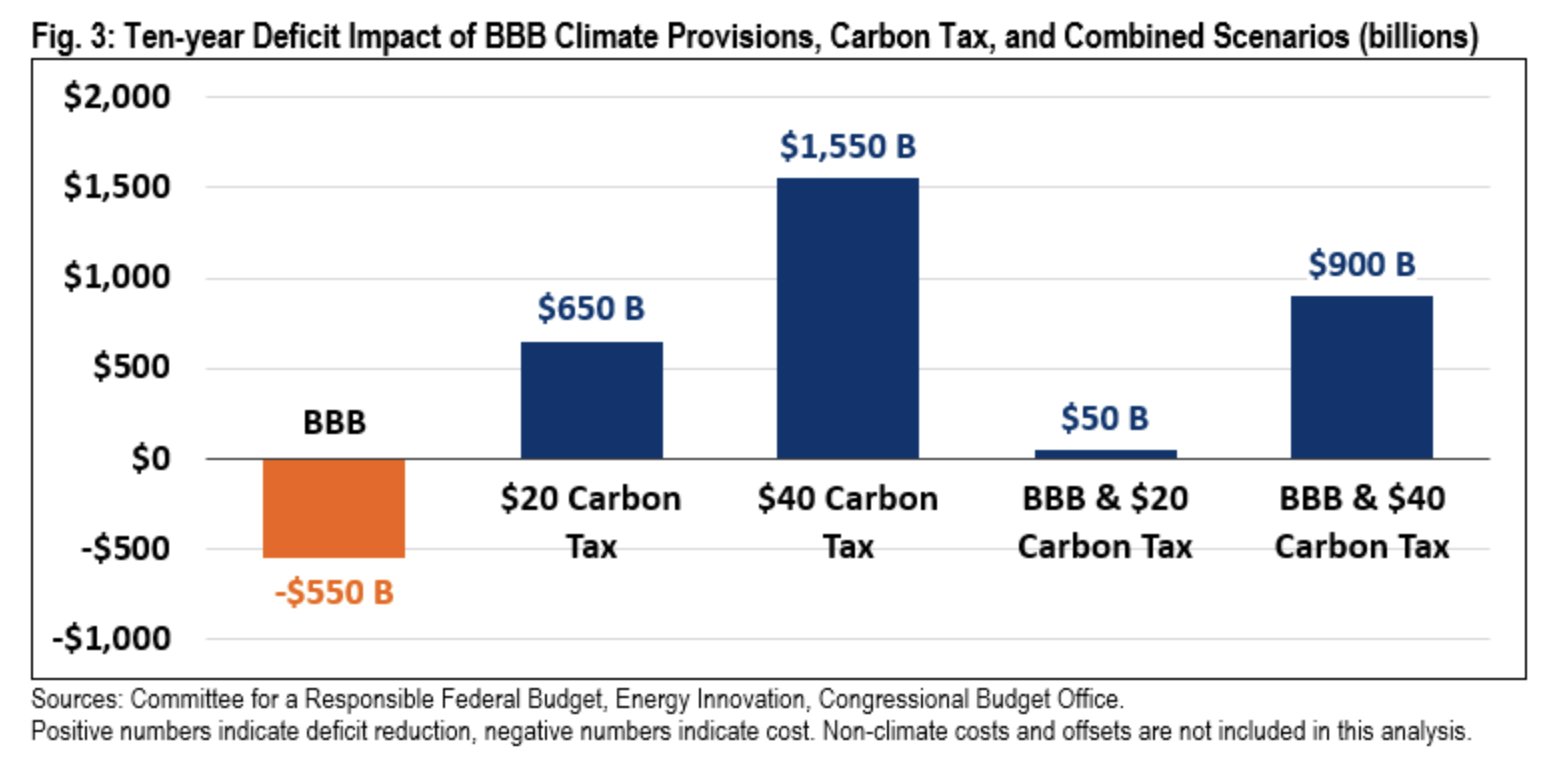

The BBB climate provisions, laden with tax subsidies for cleaner energy and transportation, would cut carbon dioxide emissions by about 34 percent by 2030 relative to 2005. The package would also cost taxpayers $550 billion over 10 years, giving heartburn to fiscally conservative lawmakers unless somehow paid for.

The CRFB report projects that a $40 carbon fee by itself would cut emissions 37 percent — better than the BBB climate provisions, but still falling short of U.S. Paris targets — while also raising $1.55 trillion in net new revenue. If married with BBB, the two policies would slash emissions by 44 percent relative to 2005, within spitting distance of America’s Paris commitment, and also raise a net $900 billion over a decade.

The findings will come as no shock to policy nerds who have followed broadly consistent (and even more optimistic) reports from research outfits such as Rhodium Group, Princeton REPEAT, and Resources for the Future. One reason is that the CRFB based its findings on the Energy Policy Simulator developed by Energy Innovation, which was also used by the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis to analyze its proposals in 2020.

What’s notable is that the founder of Energy Innovation, engineer and philanthropist Hal Harvey, has been quite skeptical about the efficacy of carbon pricing in major sectors of the economy (though he still supports a rising price on carbon). If even his model shows such powerful results from a modest $40 carbon fee, that’s a strong endorsement of CCL’s core policy.

Indeed, the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act (EICDA) would exceed that $40 price by year four. The virtue of a rising carbon fee is that it would likely outperform any of the scenarios modeled in this new report. Based on a well-reputed and peer-reviewed economic model, Resources for the Future has projected the impact on annual carbon dioxide emissions from some major carbon fee proposals introduced in Congress over the past few years. Several, including Energy Innovation Act, would drive annual emissions below 3 billion metric tons and meet the Biden administration’s emission pledge within eight years:

Annual Emissions (billion metric tons)

Source: Carbon Pricing Calculator (rff.org)

A rising carbon fee could achieve these vital objectives without deepening the national debt. By driving up the cost of fossil fuels, it provides tremendous incentives for the production of renewable energy and the manufacture of low-carbon technologies without the need for subsidies. Returning most or all the revenue to individuals, as CCL proposes, would more than offset the higher cost of energy for most households during the transition to a low-carbon economy without increasing debt. It would also fuel consumer spending, promote job growth, and strengthen political support for a durable climate policy.

Of course, where lots of money is involved, debate over how to spend it will surely follow. At least CCLers can take comfort in knowing that our carbon fee and dividend policy satisfies the core conclusion of the CRFB report:

“While climate change represents a serious threat to the security and prosperity of current and future generations, so too does our skyrocketing national debt. Lawmakers should commit to addressing the former without exacerbating the latter.”

Author’s note: Thanks to Dana Nuccitelli for his helpful suggestions on this blog.

Jonathan Marshall is an Economics Research Coordinator with CCL.